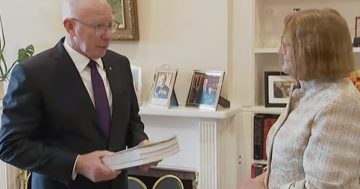

Former Prime Minister Scott Morrison: time for him to go. Photo: Screenshot.

Former Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s press conference in which he attempted to justify his ministerial power grab has only raised more questions and exposed the vulnerability of Australia’s system of government.

It was typical Morrison – evasive, slippery, full of blame shifting and contradictions, without any semblance of understanding how his actions had trashed convention and subverted the Cabinet system to accumulate unwarranted power for himself.

It was really our fault because we were clamouring for him to take control of an unprecedented situation, and it had to be kept secret, apart from Health Minister Greg Hunt, because he didn’t want to undermine the confidence of his Ministers.

And it was really OK because he didn’t have to break the emergency glass and overrule anybody, apart from Resources Minister Keith Pitt on a completely unrelated matter of an offshore drilling permit.

And that was proof that he had confidence in them, Morrison said, apart from Pitt, who didn’t understand the political consequences of allowing drilling off the NSW coast.

Morrison’s defence that there would be few people who would disagree with his decision also, quite deliberately, misses the point and diverts attention away from how he went about it.

Morrison could only offer “unforeseen circumstances” when asked why he needed to have the ministerial powers and could not adequately explain the inexplicable decision to later add Treasury and Home Affairs to his bundle of ministerial responsibilities.

The former PM targeted ministries where Ministers had the final say and could take “unilateral action”.

Hunt acquired unprecedented powers under the Biosecurity Act, powers that may have surpassed those of the Prime Minister, who was also being sidelined by National Cabinet and the Premiers.

Is that what was going on in an insecure Morrison’s mind? Could he see his power ebbing away and he needed to regain control?

The reality is the arrangements were perfectly adequate for covering the loss of a minister due to COVID and a Prime Minister should have the political heft to take an issue such as the exploration leases to Cabinet and impose their will.

But did Morrison feel confident enough to do that without fear of provoking a backlash and destabilising his own position?

If all the Ministers had found out about the PM’s secret accumulation of power, would there have been a Cabinet revolt? Probably.

Indeed, questions need to be asked of the two journalists from The Australian who sat on such explosive information for so long, keeping it from not just the other Ministers but the public until after the election and they began promoting a book.

Morrison made much of the fact that he broke no laws and sought and received advice that what he proposed was legal.

It may have been but that was never tested, while the conventions upon which the Westminster and Cabinet systems rely were discarded.

Much of Australia’s system of government, its checks and balances and distribution of power, is predicated on these conventions. Flout them and we have a house of cards.

Morrison has set a precedent, a template for dictators, that will need to be closed off by legislation.

He coopted the public service, which may have raised questions about the implications, and the Governor-General, who probably had no choice but to accept the advice of his Prime Minister, although it is not known just how much he was told.

A more activist Governor-General may have queried Morrison’s intentions, but that throws up a whole set of still unresolved questions about vice-regal powers.

Public servants can offer robust advice but cannot do much if a Prime Minister or Minister chooses to ignore it.

Nonetheless, expect any inquiry to grill those involved about how they handled the matter.

We still do not know whose idea it was, and Morrison was deliberately vague about this.

The fact is the public service was put in the position where there were parallel lines of authority, where mandarins such as Treasury head Dr Steven Kennedy and Home Affairs boss Michael Pezzullo were unaware that they were answerable to Morrison as well as their respective Ministers.

Typically, Morrison implied the controversy was another obsession of the Canberra bubble, saying Australians had more important things to worry about.

His attempt to play down the gravity of his actions should only condemn him, for what could be more important than how we are governed and how power is exercised by the people we elect?

Morrison’s position in the Parliament should now be untenable. He misled Parliament, he misled Cabinet and he showed a complete lack of respect and understanding for the conventions that underpin our system of government.

The Liberal Party may not want a by-election, so lacking in confidence is it, but Morrison should resign his seat in the national interest.

But then that is something he was not able to grasp when he embarked on and persisted with actions in his own self-interest at the expense of his Cabinet colleagues and the Parliament he swore to serve.