Running until 29 January, 2023, at the National Portrait Gallery, Who Are You: Australian Portraiture challenges conservative notions of the genre. Photo: NPG.

Hugh Ramsay was 20 when he painted his little sister, Jessie, her head tilted quizzically, large artless eyes locked onto the viewer’s and her doll hanging from one hand at her side.

Jessie with doll may have been painted more than 120 years ago, but her frank, blue-eyed gaze is harder to hold today, knowing its sad irony.

Though prodigiously talented, Ramsay lived the life of the starving artist in Paris for a time, returning to Australia gravely ill with consumption and dying at age 28, in the bloom of a brilliant career.

Jessie nursed him in his final years before succumbing to the illness herself at age 22.

Jessie with doll is one of 130 works supporting the objectives of the National Portrait Gallery (NPG) and the National Gallery of Victoria’s collaborative exhibition Who Are You: Australian Portraiture.

“A portrait isn’t just a picture of what people look like; it can encompass so many aspects of the human experience,” NPG curator Joanna Gilmour says.

“Yes, portraiture is an ancient genre but it doesn’t necessarily follow that it’s always conservative or traditional. It’s a genre as susceptible to creativity and innovation as any art practice.”

Who Are You will challenge – sometimes conspicuously – stiff, conventional preconceptions about portraiture across five major themes.

“Person and Place” explores the relationship between identity, country and place not just in relation to First Nations people but stories of migrations and colonisation and how our location plays into conceptions of who we are.

Court, 2014, by Michael Cook. Photo: NGV.

Predominantly comprising self-portraits, “Meet the Artist” demonstrates the longevity of this kind of portraiture across multiple media, conceptual approaches and eras.

“Intimacy and Alienation” documents ideas of intimacy, love, friendship and our relationships and attachments to people, while “Inner Worlds, Outer Selves” showcases the different ways artists seek to reveal hidden things about subjects, such as their fantasies and psyche.

“Icons and Identities” interrogates the idea that portraiture is fixed on public icons and demonstrates how the genre remains relevant.

“Artists have always found ways of reimagining and reinterpreting these established codes, languages and conventions of the genre,” Joanna says.

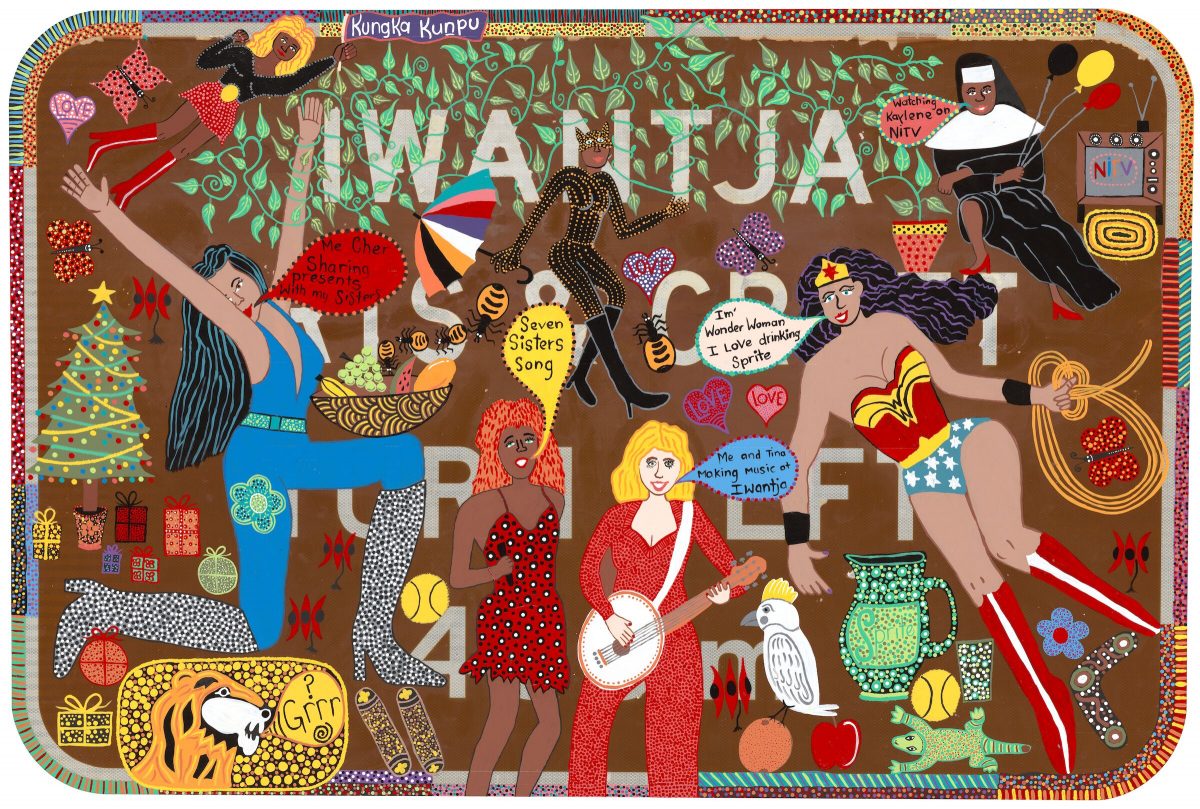

She cites Seven Sisters Song by Yankunytjatjara artist Kaylene Whiskey.

“She is known for having invented this bright, colourful pop colour lexicon for conveying traditional ancestral stories,” she says.

“Seven Sisters Song is an ancestral story relating to the formation of the Pleiades constellation. They’re imagined as contemporary pop culture icons like Cher, Dolly Parton and Tina Turner. It’s a joyful, colourful, wonderful conception of an ancient ancestral story with a modern-day iconography of characters we all relate to irrespective of our cultural background.”

Kaylene Whiskey’s Seven Sisters Song. Photo: NGV.

Joanna says visitors may be surprised that the text accompanying the portraits isn’t necessarily about the subject.

“For example, some speak to why the artist has portrayed a particular sitter a certain way,” she says.

“Henry James once said in an essay about John Singer Sargent that his portraits were characterised by his power to capture ‘unborrowed expression’, which to me means finding that way of portraying someone that defies any sort of expectation you might have of how that person would appear.”

She points to the portrait of Queen Elizabeth II in the “Icons and Identities” section of the exhibition.

“Polly Borland was one of several photographers invited to capture a portrait of the Queen for her Golden Jubilee,” she says.

“She had brought two fabric backdrops and one was a sparkly gold, glitzy material, which she had actually purchased from an Ann Summers lingerie shop … Her Majesty apparently really appreciated it.

“The resulting portrait is unconventional but lovely and certainly not how you’d expect to see a monarch represented. It really does somehow almost by accident create this strong impression of what a gracious and warm personality the Queen was said to be … For all her power, wealth and status she was someone willing to go along the ride with an artist’s vision.”

Joanna says Who Are You seeks to dismantle the “pigeonholing” of portraiture as something inflexible.

“We tend to think of it in a very literal sense – portraying the subject’s outward face … This narrow idea of portraiture is something we’re always coming up against at the National Portrait Gallery,” she says.

“This exhibition demonstrates how multifaceted it can be. It can be figurative, conceptual, abstract and exists across time and media irrespective of an artist’s style.

“I hope it will reconfigure people’s minds.”

Who Are You will run daily from 10 am to 5 pm until 29 January, 2023, at the National Portrait Gallery, King Edward Terrace, Parkes. Entry is free and bookings are not required.