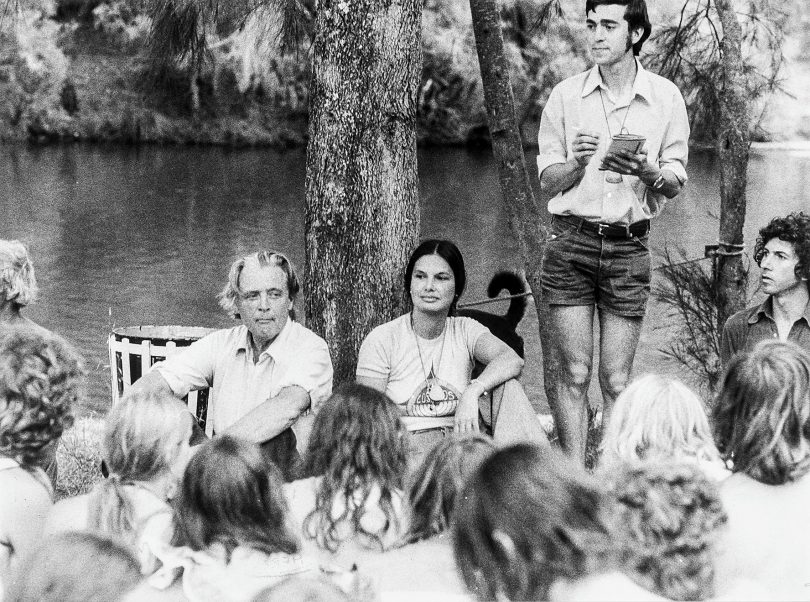

Down to Earth was held in December 1975 at the Cotter, initiated by former Deputy Prime Minister, Dr Jim Cairns. He’s pictured with his private secretary Junie Morosi. Who is that journalist in the denim shorts? Photo: CMAG.

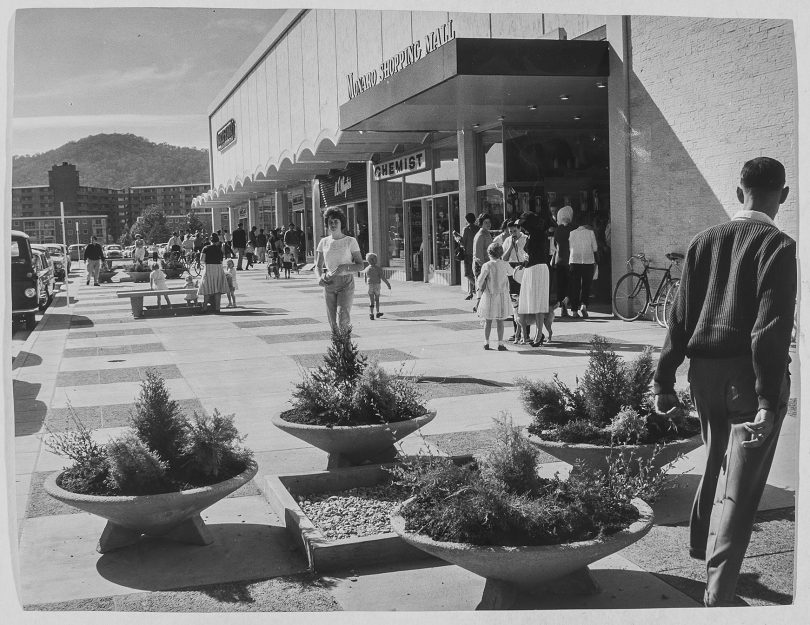

Twilight shopping at the Monaro Mall. Blokes in high-waisted pants and hats, yarning in Garema Place. New townhouses with tiny trees and kids on tricycles. And a planning meeting for the Down to Earth festival at the Cotter with Jim Cairns and his electoral assistant, Junie Morosi.

I’m at the Canberra Museum and Gallery, looking at the riches of the Fairfax Photography archives, and it’s like hitching a ride on a time machine back into our shared family history.

It’s been a long strange journey for these photographs, which Fairfax sent to the United States to be digitised in 2013, only for the Arkansas company which had secured the contract to go into liquidation. The images were then purchased by the Duncan Miller Gallery in California, who attempted to sell them online.

Senior curator Virginia Rigney moved heaven and earth to bring home the Canberra Times portion of the collection when it came up for sale. “I had so many questions about whether I could pull this off,” she says as we stand with white gloves in front of the faded boxes.

CMAG senior curator Virginia Rigney with one of the earliest archive photos, of the Scrivener Dam under construction. Photo: Genevieve Jacobs.

“I’m spending public money, there were questions about the legal title, a five-year battle over ownership, the lack of oversight about what had happened in Arkansas and the condition the works were in. But this is the photographic history of Australia in the 20th century.”

The collection was initially on the market for as much as $400 per individual image, but when the prices came down to within her budget, Rigney pounced. Images of the box labels showed “everything from obvious Canberra things like the High Court, but also the Hotel Canberra, Fyshwick, and the Dickson swimming pool.

“You could sense this was not just an archive of the great and the good or major buildings, but how Canberra represented itself to the world. This is an archive that will tell us that story.

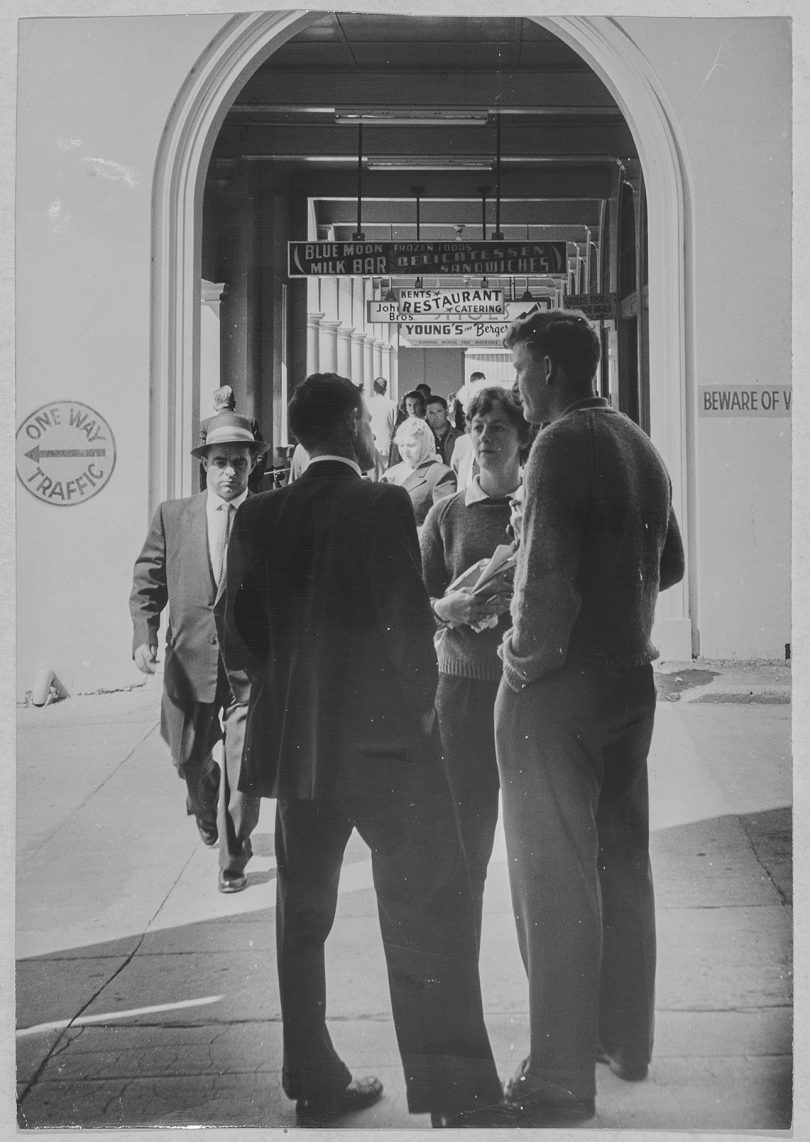

Civic, Canberra. Note the checkerboard paving which in this days, ran through the precinct. Photo: CMAG.

Rigney is particularly drawn to the fact that while Canberra has always advertised itself as a clean, safe, place of fresh opportunity, the archives are a newspaper record and therefore show plenty of grit. “There’s an image from a protest meeting of Causeway residents, all women, waiting to have their grievances heard about their living conditions. The Causeway housing was very cold, and it was pretty desperate living there, but that wasn’t the image of Canberra being shown to the world.

“Another image is long-haired hippies, and the caption says it’s students protesting the right to attend lectures barefoot. There’s a Chinese delegation in their Mao suits from the mid-seventies, standing in the Monaro mall surrounded by bemused shoppers.

“Whitlam was in power, our eyes were being opened to the wider world, but these photos also show an emerging culture of local knowledge, of interest in what the locals know.”

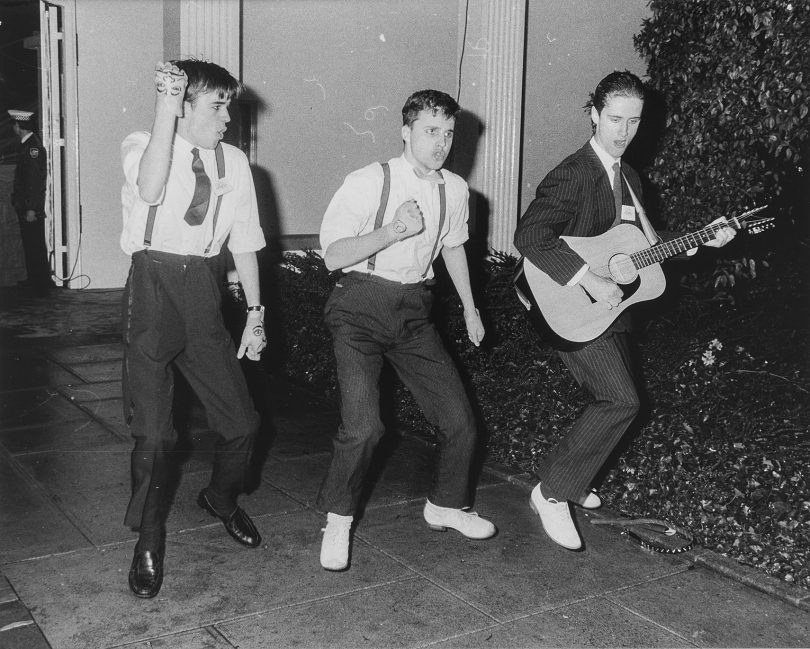

The Doug Anthony All Stars, prior to Paul McDermott. Photo: CMAG.

The provenance of the photos is also important: most are heavily marked on the rear, showing how they were used and why. There’s a group of three likely looking lads in business wear and white shoes with a query on the back – ‘rock ‘n roll group???’. It’s the Doug Anthony All-stars, sans Paul McDermott and clearly at an extremely early stage of their careers.

There are also a lot of demonstrations: intriguing images show Andrew Peacock and Bob Hawke being jostled at close quarters by angry Lebanese Australian protestors. A whole section dates from 1983, which Rigney herself remembers as a volatile year when the call would go out at the ANU to storm the National Press Club, where the US Secretary of State might be speaking.

Undated image of the Sydney Building, showing the Blue Moon Milk Bar in the background. Photo: CMAG.

The first step is to catalogue and store the collection with the help of conservation students from the University of Canberra. Two exhibitions are planned, and the demonstration images, in particular, will fit well with the forthcoming CMAG activism exhibition. Rigney also plans to work with the arts community on connecting with some of the images and bringing a contemporary eye to the collection.

“The Canberra Times has changed hands many times, so it’s a bit miraculous this archive has stayed together,” Rigney says. “They’re not just documents, there are some stunning photographic images. Canberrans can identify and place themselves in the history of the community – that photo of twilight shopping at the Monaro Mall could have been me and my family. This is the story of us.”