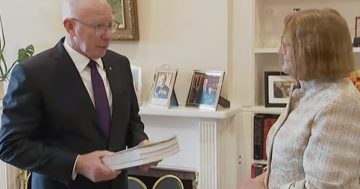

Robodebt Royal Commissioner is Ms Catherine Holmes AC SC. Photo: Screenshot.

Let’s talk about royal commissions because there’s a lot of misunderstanding about what they are, how they operate, and how they should be treated both by casual observers, commentators and interested parties.

Is a royal commission an actual court?

Well, no, not exactly. But let’s not be fooled by that.

A royal commission has broad powers – coercive powers to compel someone to appear, give evidence, or otherwise participate in its inquiry.

It can summons witnesses to produce what it might consider evidentiary documents.

There are very few grounds on which someone can refuse to give evidence at a royal commission, and it is a serious offence to intentionally provide false or misleading evidence to one, or to intentionally insult, disturb or disrupt one.

In Australia, royal commissions are the highest form of inquiry on matters of public importance.

They can refer matters to law enforcement agencies, suggest legal pursuit and recommend how things should change.

A royal commission is a form of non-judicial and non-administrative governmental investigation that is only established in exceptional circumstances and with tightly specified terms of reference.

They are so independent of government that once one is established, through the issuing of Letters Patent by the Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia under the Royal Commissions Act 1902 (Cth), it can almost never be stopped even by the government that instigated it.

Commonwealth royal commissions can only inquire into matters related to the Commonwealth’s responsibilities.

They are sometimes seen as political because it is often one side of politics calling an inquiry into something the other side did when it was in office.

The terms ‘witch-hunt’ and ‘kangaroo court’ will sometimes be used by a disgruntled opposition freshly turfed off the Treasury benches, yet royal commissions are almost always conducted professionally, thoroughly and at arm’s length from government.

Which brings us to the Royal Commission into the Robodebt Scheme, headed by former Queensland Supreme Court Justice Catherine Holmes AC SC.

If ever there was an issue crying out for a royal commission, Robodebt is it.

Now in its last week of hearing witness evidence, this royal commission has uncovered a great deal while also respecting the dignity of all witnesses.

Similar can be said of the witnesses themselves and how they have approached the inquiry.

This is far too important a subject with which to be playing political games, which is why a continued commentary around the evidence is not such a wise thing.

This brings us to the Minister for Government Services, Bill Shorten.

Sure, this is Shorten’s portfolio area, but each time he pops up to condemn a former Coalition minister after an appearance before the inquiry, the more he invites accusations of political bias in it.

Throughout the royal commission, Shorten has called media conferences and made statements to suggest that the former Coalition government has squandered opportunities to use the inquiry to apologise for Robodebt.

He has described Stuart Robert’s evidence as “peak bizarre” and Scott Morrison’s as “peak vintage Morrison” and a “trainwreck”, while also claiming Marise Payne’s appearance was more plausible than her former boss’s.

He is doing his best to make this particular royal commission look like a partisan inquiry.

Which is a pity, because it’s not.

Media and other so-called pundit commentaries already suggesting who will be the victim/s of the inquiry – before it has even finished hearing evidence and months before it reports to the government – are undignified enough.

But when senior government ministers buy into (lead) opinionated discourse over evidence while the inquiry continues, they can damage the very credibility of the investigation itself.

Shorten is not the only one doing it. He’s just the most prominent and regular government MP running Robodebt commentary.

Of course, the commissioner and counsels assisting won’t be affected one bit by any political debate, but that’s not the point.

And it’s not the intent of the commentary. The royal commission is not the target audience.

No, royal commissions aren’t actual courts, so sadly, the norms of sub judice don’t quite apply.

But wouldn’t it be good if everyone – most notably our elected officials – gave them the same courtesy they must legally give to court cases?

That is, let the evidence be reported and decline to comment until the inquiry has done its job.