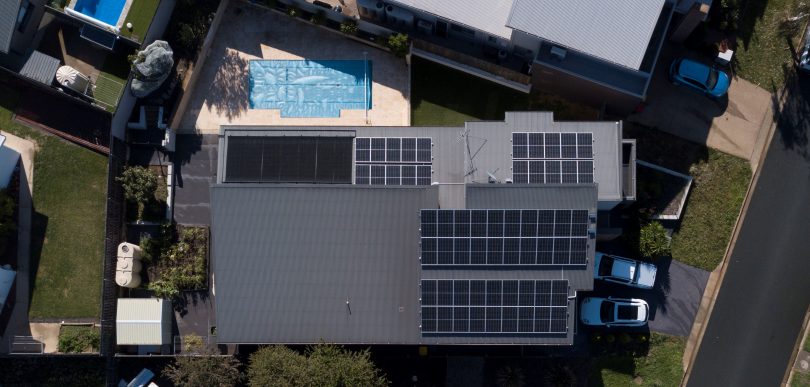

Solar panels are popular and make money for owners but will the boom continue with a solar tax? Photo: Supplied.

A proposal for a solar tax or charge for solar panel owners to export the power they generate to the grid to prevent ”traffic jams” in supply seems again to cast a shadow over the take-up of renewable energy in this country.

Interest from potential panel owners is already falling and those with panels installed are talking about switching them off at strategic times.

The Australian Energy Market Commission, which made the recommendation, says that energy companies may have to refuse grid access to solar panels to maintain its stability without a change to the rules, which would cost them even more.

AEMC also argues that Australia needs a more equitable system so non-solar consumers are not subsidising panel owners and that overall bills would fall.

Its modelling shows typical panel owners would only lose about $100 of their average $900 income.

It also says that the current arrangements were not established for a two-way system. A charge would allow networks to tailor their own pricing mechanisms to ensure investment in parts of the grid where needed.

Australia, and Canberra in particular, has one of the biggest take-ups of solar power in the world. AEMC says it wants to ensure more access to solar, not less.

“This is about creating tailored options, not blanket solutions,” AEMC chief executive Ben Barr said in a statement.

“We want to open the solar gateway so more Australians can join the 2.6 million small solar owners who have already led the way. But it’s important to do this fairly. We want to avoid a first-come, best dressed system because that limits the capacity for more solar into the grid.”

AEMC, which has been wanting such a charge for years, based its ruling on submissions from energy companies and welfare groups. But Victoria’s Total Environment Centre also argued that the current system did not provide any incentive for networks to accommodate higher solar and battery exports.

The charge does not seem a lot, although where it may end is unknown, and the inequities within the current structure create an energy divide.

But it reeks of cost-shifting by energy companies who have already reaped the benefits from gold-plating poles and wires, and one wonders why they should not be investing in necessary upgrades anyway.

While a small fall in power bills would be welcome, it would do nothing to bridge the gap between homeowners who can afford to install solar and others, especially renters.

In fact, it would likely deter landlords who might consider installing them.

Commercial generators are not charged for access to the grid, so many panel owners also find the proposition hypocritical.

There are also doubts about the extent of the problems facing power networks, which have been accused of exaggerating their claims to boost arguments for charging solar panel owners.

The solar revolution has been underway for years now, and the issues of grid flow and stability have been well flagged, but instead of reforming the system to accommodate the increasing solar capacity, the response has been to wait until problems occur.

This seems more like tweaking the system than modernising it and looks like yet another example of putting up a barrier rather than opening the gateway to greening the grid.

Like the new road-user taxes on electric vehicles, it sends the wrong message to a community wanting to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Perhaps the privatisation of the electricity industry was not such a smart option.