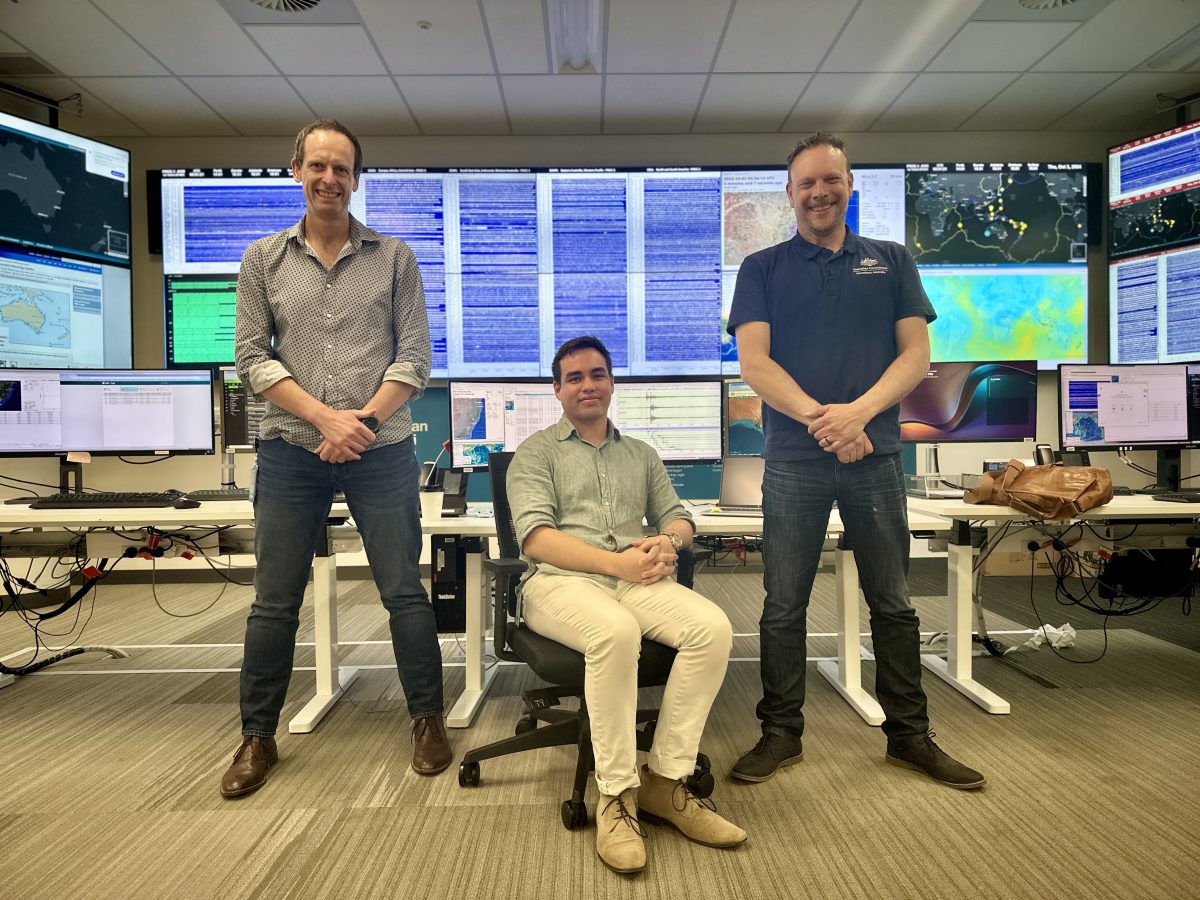

Dr Trevor Allen, Alex Dao and Allen Earl from the National Earthquake Alerts Centre (NEAC) at Geoscience Australia. Photo: James Coleman.

They typically take the form of a fridge-looking box in the middle of a paddock, with a couple of solar panels for power and maybe a satellite dish.

They’re called seismic ground monitors, and they mean that there’s not a mine blast that goes off anywhere in the country the person sitting behind the desk at Geoscience Australia doesn’t know about.

Or, more to the point, an earthquake.

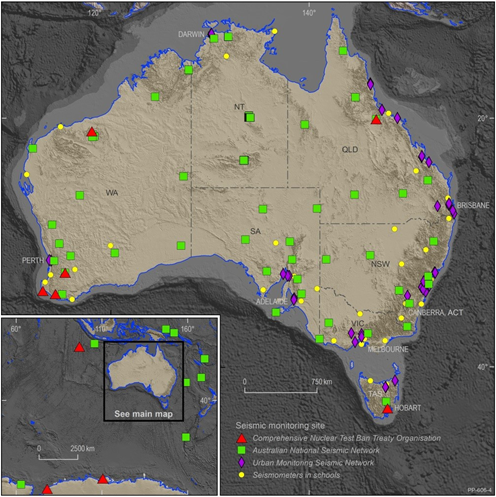

Geoscience Australia looks after more than 100 of these seismic monitors across Australia, the Pacific islands, Southern and Indian Oceans, and our Antarctic territories that, together, form the Australian National Seismograph Network (ANSN).

Another 500 stations feed information in from each of the world’s continents and major oceans.

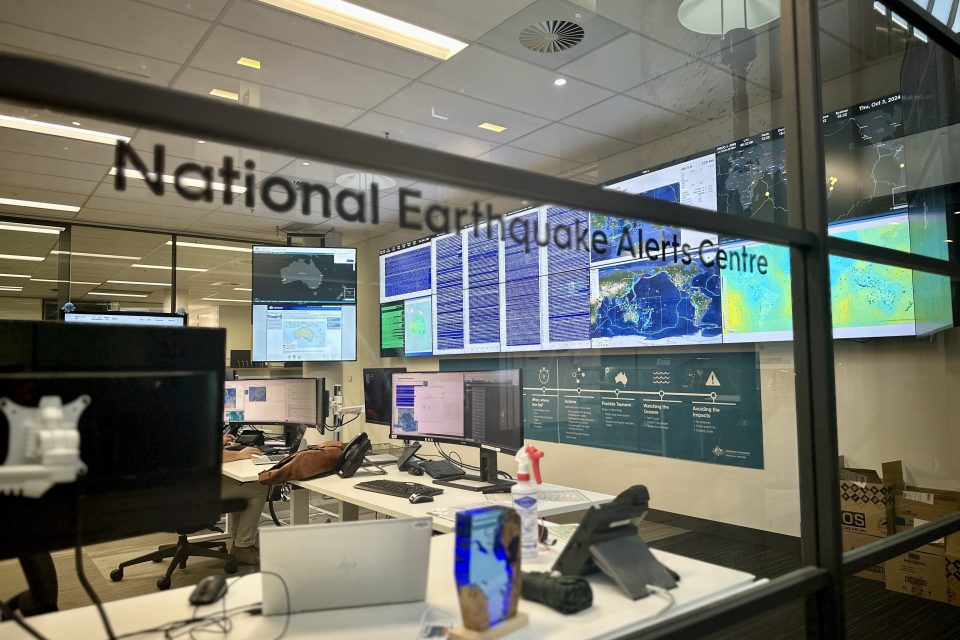

Ahead of Earth Science Week 2024, running from 13 to 19 October, Geoscience Australia gave us a private tour of its nerve centre – the National Earthquake Alert Centre (NEAC), at its headquarters in Symonston – where monitoring earthquakes is a full-time, 24/7 job.

A seismic monitoring station, as part of the Australian National Seismograph Network (ANSN). Photo: Geoscience Australia.

As a whole, the federal government agency is tasked with “monitoring and evaluating the earth”, according to Strategic Science director Dr Verity Normington.

“Geoscience Australia does a lot of work with other agencies like the Bureau of Meteorology around tsunami warnings and CSIRO for ground-water resources, and we look at prospecting of natural resources and undertaking geological surveys,” she says.

A particularly large part of the workforce is dedicated to getting that blue positioning dot on your Google Maps app as accurate as it can be, and involves space and satellites.

Geoscience Australia Strategic Science director Dr Verity Normington. Photo: James Coleman.

“And it’s not just about today, because once we go to autonomous cars, we really need to know exactly where the gutter is or where the tree is, and there’s a big difference between five centimetres and 20 centimetres,” Dr Normington explains.

“A lot of this work is done on the surface, so we have receivers on the ground that talk to satellites, and the more receivers we have, the more precise our locations.”

The headquarters also include an education centre, which welcomes more than 10,000 students and teachers and between 2000 and 3000 other visitors every year. Items on display include the only piece of moon rock in the Southern Hemisphere, on loan from NASA.

“We have all sorts of items from across the country to increase the understanding of earth science and its value to everything we do.”

The world’s tectonic plates, floating on the red hot molten rock we called magma, are obviously always rubbing up against each other, usually with movements too subtle for humans to detect.

So when NEAC really cares is when they get a spike on the charts. Any seismic movement magnitude 3.5 or above here in Australia, or magnitude 5 or above anywhere in the world, prompts an earthquake alert.

But before this can be published, there’s a lot of work to be done.

The first point of order is to check if it was real. The complex computer algorithms hunt for changes in the baseline readings, so cases of “environmental noise” – such as a mine blast – will slip in occasionally.

A map of the Australian National Seismograph Network (ANSN). Photo: Geoscience Australia.

That’s why there’s always at least one staff member, along with a qualified seismologist and IT administrator, on-site at all times to look for anomalies.

Another good way of working out whether an earthquake is real is if they start receiving “felt reports” from the public through the Geoscience Australia website. For instance, during a magnitude-5.9 quake in Victoria in 2021, there were 44,000 reports submitted within 10 minutes.

The aim is that within 10 minutes of a high reading coming through, the National Emergency Management Agency’s ‘National Situation Room’ (NSR) in Barton knows about it, so they can brief local emergency services and media if need be.

If there’s the potential it could trigger a tsunami, there’s another phone marked ‘BOM’ that serves as a hotline to the Bureau of Meteorology. The BOM is provided with all the data, and then does its own assessment and issues a tsunami alert if need be.

Within 30 minutes, an earthquake alert is published to the Geoscience Australia website.

In the case of a power outage or technical hitch, there’s another smaller setup at the NRS office the whole operation can relocate to. Every week, staff run a scheduled handover to check everyone’s familiar with what they have to do and all the systems are operating correctly.

The information isn’t just live either – it’s all mapped and recorded to form a seismic history for each part of Australia. This is particularly handy for developing building codes, so developers know how much a site may move before putting anything permanent on it.

So, thanks, NEAC team – we all have a lot to thank you for.

Geoscience Australia is open 9 am to 5 pm, Monday to Friday. Entry and parking are free.