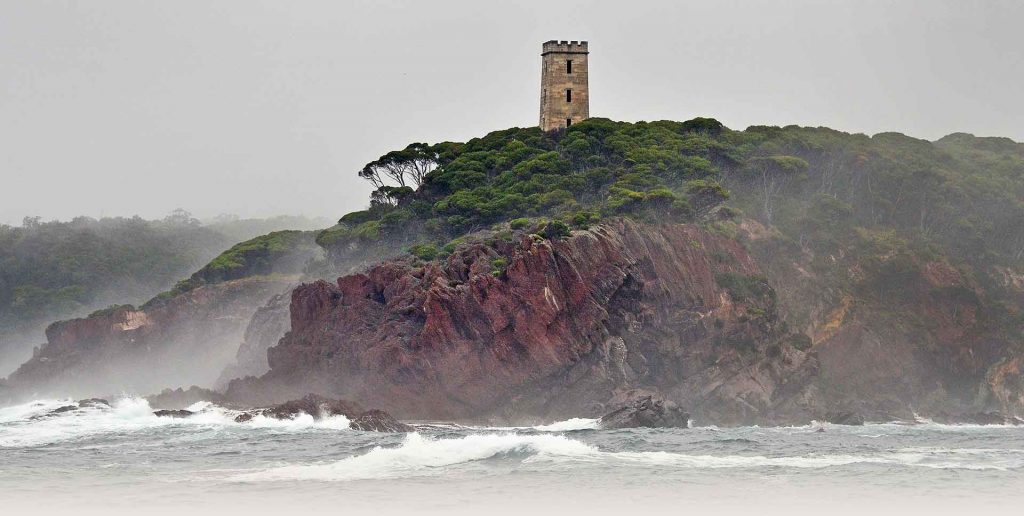

Boyd’s Tower, south of Eden in Ben Boyd National Park. Photo: Sapphire Coast Tourism.

Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s remark on 11 June that Australia was “a pretty brutal place, but there was no slavery”, in response to Black Lives Matter protests across the country – which he apologised for afterwards – has been followed by a push in some parts of the community to reconsider the names of popular NSW South Coast landmarks.

The suggestion from those arguing for name changes is that it’s time to stop rewarding the memory of early white settlers in Australia and explorers at places such as Ben Boyd National Park, Mount Kosciuszko and Mount Imlay.

Last year, it was suggested that Mount Kosciuszko be known by a dual Indigenous name, Kunama Namadgi, meaning snow and mountain in Ngarigo language. However, it has not been officially approved because the name is contentious with some Indigenous groups.

So what’s the thinking behind these calls?

Writer and naturalist John Blay, who has worked with Eden Local Aboriginal Land Council on documenting the Bundian Way, wrote in a social media post on Wednesday:

“Ben Boyd is celebrated in the name of national parks and towns in the region. There have been Aboriginal calls to rename the national parks and, for all we know, nothing’s been done. There has been terrible silence. Do we need to grant Ben Boyd our highest accolades and remembrance? He was the worst of exploiters and tried to enslave the Aboriginal people of Twofold Bay.”

Names have meaning, says Yuin man Graeme Moore, who, in his work with the Biamanga Board and his community, has advocated for a return to Aboriginal names for local landmarks.

“All our names have ripples of meaning and connectivity,” he said. “Take, for instance, Merimboola, or Merimbula as we now know it. It means place of the red belly black snake, but also has its roots in the bloodwood.”

Having a chunk of land named in honour of Ben Boyd, a Scottish grazier who lived until 1851 and was known for exploiting Indigenous Australians and Pacific Islanders for labour reinforces that period of colonial history, he thinks.

“Naming a place gives an understanding of what’s there,” said Mr Moore. “Changing the name is about appreciating there were people before Ben Boyd.”

Using Aboriginal place names in daily life helps young generations look at the past and to the future, he added.

“Names give us all an understanding of what’s there,” said Mr Moore. “It’s all there; the evidence is everywhere you look – all our special camps, our burials, you just have to know where to look or be respectfully shown.”

Merimbula resident Christine Garrison is supportive of the move to change the name of Ben Boyd National Park.

“We’ve all known the park by this name for so long and many of us have good memories associated with the name, but it’s time to change,” she said. “Ben Boyd is not someone we need to remember this way. If we all associate this beautiful place with an Indigenous name, it helps us all recall and respect the people who have lived there for thousands of years.”

John Blay spoke of Ben Boyd’s bitter end:

“The only poetic justice in all this is that on another exhibition to the Pacific Islands to round up more victims, he went ashore and was never seen again by the crew of his yacht. Is this a man we are proud of? Is this a man Scott Morrison would approve of, considering his comments last week? I would happily see his name wiped off our maps. His infamy should perhaps only be kept alive in our history books to ensure none of his deplorable activities are ever repeated.”

Mr Moore asked if names have meaning we absorb every time we speak or write them, what does Ben Boyd mean?

He said at the north end of Ben Boyd National Park, across from the Pambula River mouth at Toalla, for example, there are different Indigenous names for different parts of the park.

“The name is the beginning of your journey,” he said.

Original Article published by Elka Wood on About Regional.