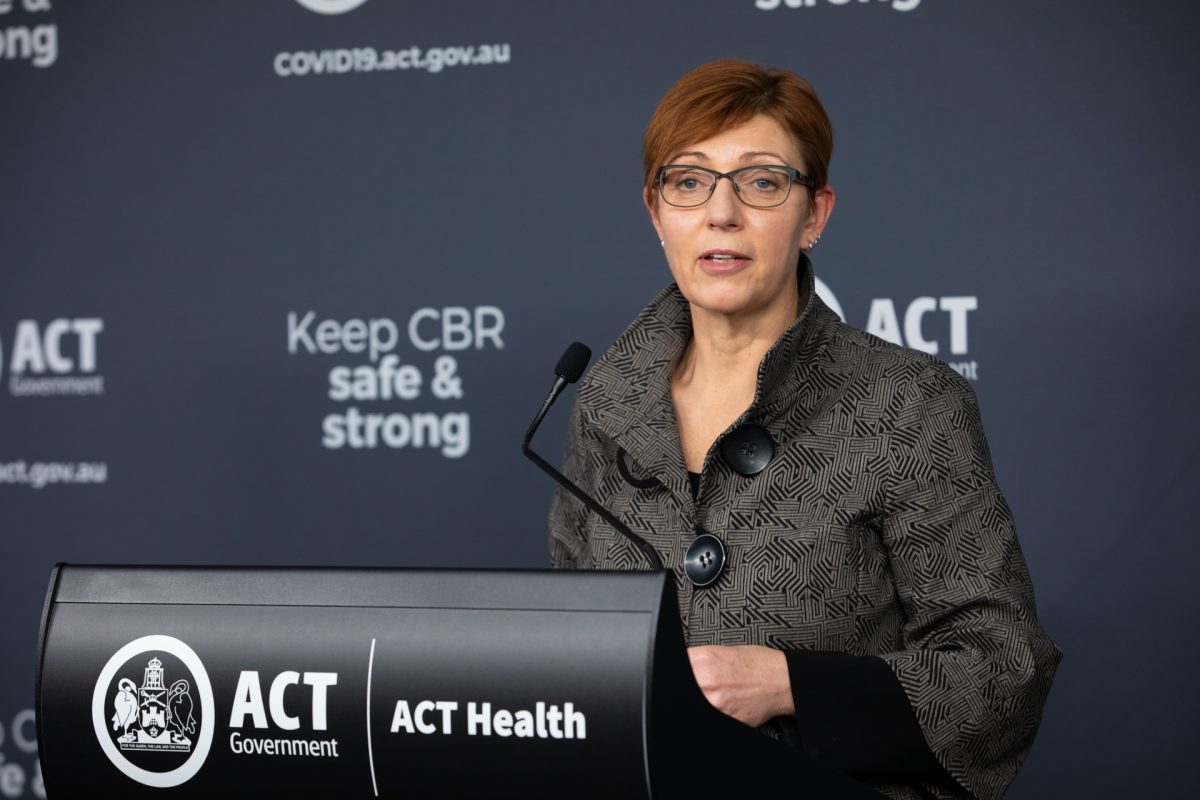

Minister for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs Rachel Stephen-Smith apologises for the hurt caused during the consultation process for a treaty between the ACT Government and the traditional owners of the region. Photo: Thomas Lucraft.

The territory’s Minister for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs has apologised for the hurt caused during the first steps towards a treaty between the ACT Government and the traditional owners of the region.

In a statement, Rachel Stephen-Smith thanked those who had participated in consultation so far but acknowledged it had not gone far enough.

She confirmed the government was not rushing to develop such a treaty.

In keeping with a budget commitment, Chief Minister Andrew Barr and Ms Stephen-Smith earlier this year announced Professor Kerry Arabena would facilitate preliminary talks about what a treaty would mean for the ACT’s traditional owners.

Those talks produced a report that outlined a 10-step process for the treaty, which it said had been endorsed by Ngunnawal people.

The 10 steps included the United Ngunnawal Elders Council (UNEC) agreeing to how negotiations would take place, the Legislative Assembly passing a Treaty Act and the government and UNEC agreeing on a reparations package.

They could include one-off payments for historical wrongdoings paid to elders and be used to set up a fund to ensure wealth would be handed on to younger generations.

Expanding available land and development opportunities to Ngunnawal people, for housing, farms and solar farms, was also recommended.

A Ngunnawal family register would also have to be created, the report stated.

UNEC also supported subsidising private health coverage for Ngunnawal people and a brokerage fund to ensure access to cultural healing services.

Ms Stephen-Smith said the report included powerful statements of aspiration and a commitment to self-determination.

But she acknowledged the report’s content and concerns would cause distress for community members, particularly those individuals and families who had not been consulted in this early process.

She assured those people there was no timeline for moving forward and the government had not made decisions or commitments to any individual or family group about what the treaty would look like or how it would be realised.

“I have also heard from some individuals and families that they do not believe treaty is the right path forward for the ACT. These voices must have the opportunity to be heard,” she said.

Not all Ngunnawal families are represented by UNEC.

Honorary Research Fellow at the Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research Dr Ed Wensing, who wrote a substantial analysis on native title issues for the Australia Institute last year, said native title claims were likely to be the first step in establishing a treaty.

The Ngunnawal Nation Traditional Owners Network Group announced last month its intention to do so over the entire ACT and some parts of NSW.

But Dr Wensing said the process would be a complicated and lengthy one, given the need for independent genealogy and anthropological analysis to prove the claimant’s ongoing connection to the land.

He’s also argued the 2001 Namadgi National Park Agreement signed between the ACT Government and Ngambri/Ngunnawal parties has helped actively restrict native title claims since.

He said there was also the matter of working out which groups had claims over the land and whether there were any overlapping claims.

For example, while the ACT Government recognised Canberra as Ngunnawal Country, this had been criticised as a “one tribe” policy by members of the Ngarigu people and members of the Ngambri clan.

Professor Arabena’s report acknowledged that if successful, this native title claim would help expand the land held by the Ngunnawal people.