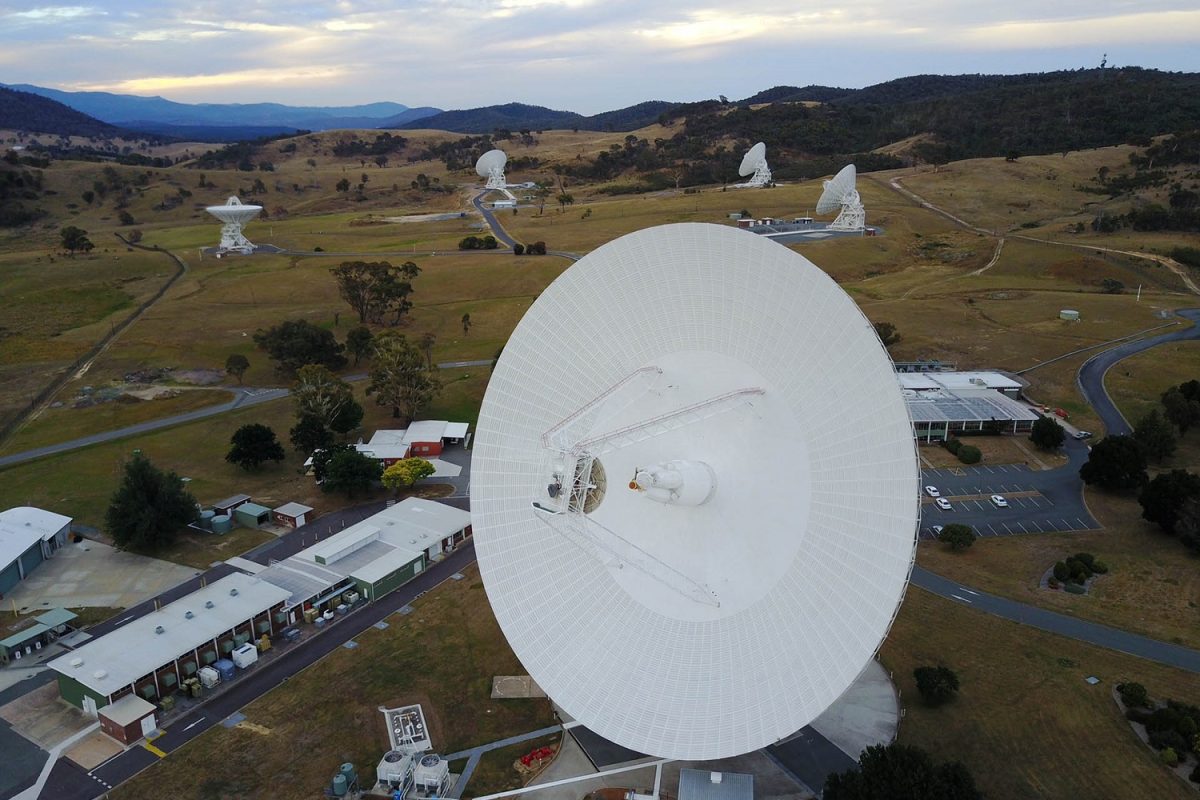

The Canberra Deep Space Communications Complex at Tidbinbilla, with antenna DSS-43 in the foreground. Photo: CSIRO.

The Canberra Deep Space Communications Complex at Tidbinbilla has successfully detected a signal from NASA’s Voyager 2 spacecraft, which had been thought lost.

The spacecraft was accidentally sent a wrong command in mid-July instructing it to turn its antenna away from Earth, which meant connection to it was lost. But a “heartbeat”-like signal was detected overnight on Tuesday (1 August) by the CSIRO-operated antenna at Tidbinbilla, leading to hope that connection with Voyager 2 can be re-established.

“The big dish here in Canberra – Deep Space Station (DSS) 43 – is the only dish in the world capable of communicating with Voyager 2, and has successfully picked up a carrier signal from the spacecraft,” Glen Nagle from CSIRO Space and Astronomy told Region.

“This is effectively the heartbeat of the spacecraft – no data and no information. It’s purely a transmission from the craft to say it’s there,” he added. “So that is really great news.

“What will happen now is the NASA science and engineering team for the Voyager mission will relay commands through our antenna to Voyager 2 to try to lock into the system’s computer, and get the antenna pointed back towards Earth.”

Great news! Our 70-metre dish, Deep Space Station 43, has detected a carrier signal from @NASAVoyager 2. Next up, we’ll transmit commands in an attempt to realign the spacecraft’s antenna with Earth. #DSS43 #Voyager2

🌏📡〰️〰️〰️〰️〰️<|)[] https://t.co/RkwVpBxvGv— CanberraDSN 📡 (@CanberraDSN) August 1, 2023

The reason DSS-43 is the only antenna capable of communicating with Voyager 2 is because the spacecraft exited the solar system below or to the ‘south’ of the solar system’s plane, so other deep space tracking network antennas in Spain and California are not able to see the area of sky Voyager 2 is travelling in.

“Voyager 2 is currently visible in our southern skies, and is about 20 billion kilometres from home,” Mr Nagle said. “That’s about five times further away than the orbit of Pluto. Effectively the spacecraft continues its own outward journey relative to the solar system, racing away from us at about 17 kilometres per second, or about 1.4 million kilometres per day.”

By comparison, a modern jet airliner travels at about 900 km/h, while objects in earth orbit can travel up to 36,000 km/h.

graphic showing the trajectories of Voyagers 1 and 2 as they explored the solar system in the 1980s. Image: NASA.

Voyager 2 was launched in August 1977 from Cape Canaveral in Florida on a mission to explore the gas giant planets of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune, and it visited these planets and their systems of moons in 1979, 1981, 1986, and 1989, respectively.

After that, Voyager 2 used a gravity slingshot from Neptune to exit the solar system in a trajectory below the planetary plane, and it has continued to send data back to NASA ever since. Its sister craft, Voyager 1 was launched a couple of weeks after Voyager 2, and exited the solar system above or ‘north’ of the planetary plane after visiting Saturn in 1980.

“Voyager 2’s original mission was to do this grand tour of the solar system, finishing its task with an encounter with Neptune in 1989,” Mr Nagle explained. “But here we are nearly 34 years later, and that spacecraft is still going!”

The trajectory took Voyager 2 well away from Pluto and the Kuiper Belt, which is effectively another asteroid belt beyond Neptune and Pluto’s orbits.

Concept art of Voyager 2 travelling through space. Image: NASA.

“Voyager’s extended mission was designed to encounter the outer edge of the influence of the energy of our sun – the solar winds and the sun’s magnetic field which surrounds our entire solar system,” he said, likening the sun’s influence to a bow wave in front of a ship as the solar system moves through the Milky Way galaxy.

“Both Voyagers were able to travel through that shockwave and measure its intensity and the flow of energy in the magnetic field and how it changes. And now, they’re ahead of that wave and are in the ‘clear air’ of interstellar space, the space between the stars, and for the first time are measuring that environment.

“Nobody expected us to be able to that so soon, because nobody expected spacecraft to last this long and to go this far!”

The signal received by DSS-43 on Wednesday morning had been travelling through space at the speed of light for about 19 hours. To put this into context, our sun is about nine light minutes from Earth, and the next nearest star – Proxima Centauri, which is one of the two stars commonly called ‘The’Pointers’ near the Southern Cross constellation – is 4.2 light years, or nearly 2000 times further away than Voyager 2’s current position.