Professor Carolyn Briggs, David Tournier, Professor Brian Martin, Julian Rutten, Alexander Holland, and Dr Stanislav Roudavski, Wominjeka Djeembana Indigenous research lab, Monash University; Deep Design Lab, and The University of Melbourne, Kummargi Gadhaba Yulendj Tarrang (The knowledge of the trees is rising up) Digital video. Photo: Supplied.

There are over 700 recognised art prizes in Australia – so why does the Waterhouse Natural Science Art Prize really matter? It is not the most prestigious, the richest, the oldest or the best publicised.

The main reason it matters is that it’s unique. While various botanical and wildlife societies run awards for botanical drawing and others focus on birds and zoological illustration, only the Waterhouse offers a broad-church approach dealing with all aspects of nature and their intersection with science.

Established in 2002 and first awarded in 2003, it was named after the South Australian Museum’s first curator, Frederick George Waterhouse. The biennial art prize is hosted by the South Australian Museum in Adelaide and the winning entries and a selection of the finalists are subsequently exhibited at the National Archives in Canberra.

From the 10 or so iterations of this prize that I have seen in Adelaide and Canberra, this is not one of the most interesting. In part, the difficulty lies in the criteria for entry into the prize and especially the exclusion of photography as an acceptable medium. Entries where the photographic process is involved may be considered, but those where the photograph is the end product are rejected.

Andrew Gall, Coming Together, 3D printed porcelain, 15 x 15 x 15cm. Photo: Supplied.

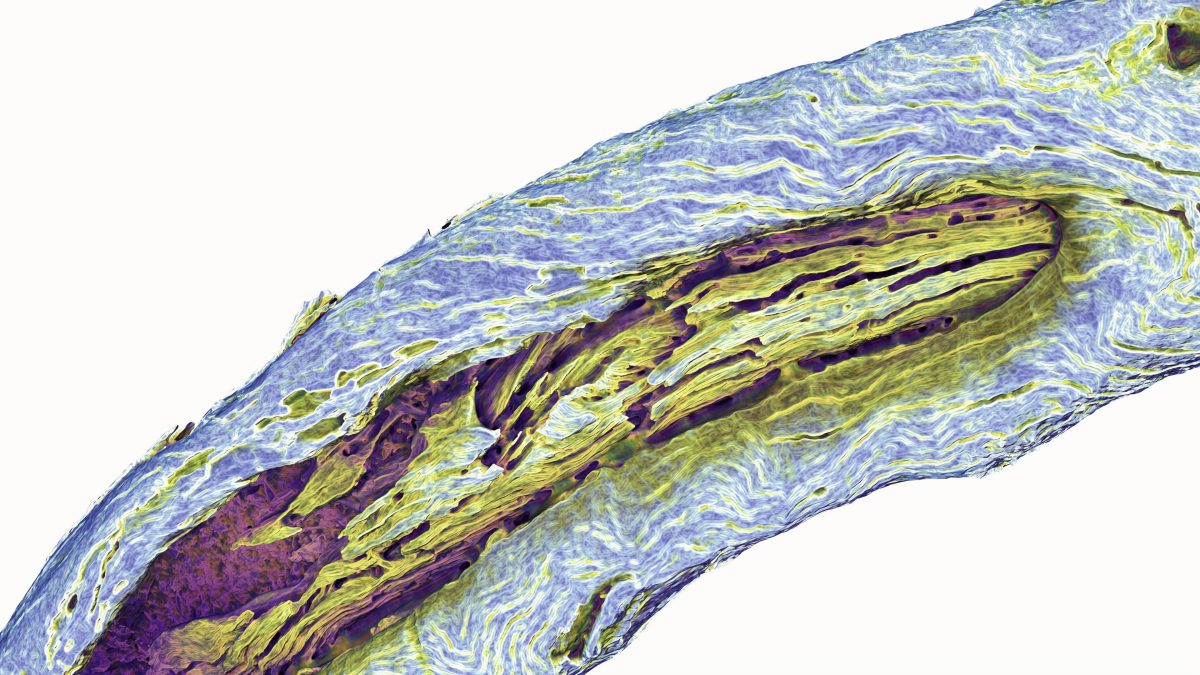

Surely, that horse has well and truly bolted, and in fact, one of the most interesting pieces in the exhibition is the six-minute digital video, Kummargi Gadhaba Yulendj Tarrang (The knowledge of the trees is rising up). It is an intriguing, immersive collaborative piece by Professor Carolyn Briggs AM, David Tournier, Professor Brian Martin, Julian Rutten, Alexander Holland and Dr Stanislav Roudavski. They employ laser scans to create a digital model of a tree marked by Kulin ancestors who, from its bark, made canoes, shields or coolamons.

The artist notes, “Analysing millions of points produced by laser reflections, we reveal meaningful features of the tree, including cultural markings, wood anatomy, traces of past fires, and the work of insects who called this tree home. These features refer to holistic ecologies where all share and nothing dies.”

Another artist who employs photographic strategies is Andrew Gall, the winner of the Emerging Artists’ Prize. His piece, Coming together, employs a 3D printer through which he has replicated sea shells that have been strung into a traditional kanalaritja shell necklace. The comment is about the threat posed by climate change and rising ocean acidity to cultural traditions. One may applaud the message but remain unmoved by the art object.

Jenna Lee, Grass Tree – Growing Together, pages of Aboriginal Words and Place Names, book binding thread, book cover board, florist wire, 55 x 30 x 25cm. Photo: Supplied.

The grand winner of the Open Prize, Jenna Lee, has moved to a very low-tech strategy for her Grass tree – Growing together. She attacked what she described as a “flawed” dictionary of Aboriginal words with a pair of scissors to create a couple of miniature grass trees.

Lee observes, “I draw parallels between First Peoples’ linguistic resilience and this plant’s ability to rise from ashes.”

Again, it is a triumph of ideology over artwork and slightly disappointing when one recalls her outstanding papercraft installation in the Melbourne Now exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria last year.

Charmain Hearder, Eolian Saltation, Ceramic sculpture, 72 x 15.7 x 88cm. Photo: Supplied.

A piece that I found most memorable was Charmain Hearder’s ceramic sculpture Eolian Saltation, which recorded the movement of wind over sand to create ripples. Although one immediately recalls Marea Gazzard’s ceramic hillscapes, Hearder goes a step further and, through a subtle combination of different colour clays and the rhythmic manipulation of surface textures, creates her wonderfully evocative and sensual sand dunes.

Jeffery Mincham, Elegy of the shore, ceramic, 62 x 120 x 70cm. Photo: Supplied.

Another successful and evocative ceramic installation is Jeffery Mincham’s Elegy of the shore, where again we are examining that liminal space where the water touches the shore and different realities combine and leave their traces.

The Waterhouse Natural Science Art Prize 2024 may not be an outstanding exhibition, but it does contain works that are memorable and that explore the porous boundary between art and the sciences. I always find it amusing that in Adelaide, the Waterhouse show is a ticketed event that attracts long queues of visitors, while at the National Archives, it is free and attracts only a modest visitation. Perhaps if the Archives start charging, the crowds will come.

Waterhouse Natural Science Art Prize 2024, National Archives of Australia, Kings Ave, Parkes. Closes 27 October, open daily from 9 am to 5 pm. Admission is free.