Dr Bjorn Sturmberg is a research fellow at the Australian National University (ANU). Photo: ANU.

Dr Bjorn Sturmberg credits a particularly engaging physics teacher for getting him to where he is today.

“He was Dr Butler, and from memory, I had him both year 11 and 12, and he was a phenomenal teacher, really inspirational,” he says.

“Just as one metric of the impact he had, there was a good number of us in my year that went on to do science degrees at Sydney University, and at least three of us who did PhDs.”

Dr Sturmberg, now a senior research fellow at the Australian National University (ANU), was named ACT Emerging Scientist of the Year this week for what Chief Minister Andrew Barr described as “important work”, exploring how electric vehicles (EVs) and batteries could integrate with the power grid.

“I would like to congratulate Dr Sturmberg on this incredible achievement and the extraordinary work that has seen him awarded 2024’s ACT Emerging Scientist of the Year,” Mr Barr said.

“His research aims to have immediate, real-world impacts to accelerate the transition to clean energy and steer this transition towards fairer and more equitable outcomes.”

Dr Sturmberg moved to Canberra in early 2019 to join the Battery Storage and Grid Integration Program at the ANU.

Created with the help of seed funding from the ACT Government in April 2018, the program aims to get the individual “building blocks” of solar panels, wind farms, EVs and batteries working together reliably enough to replace fossil fuels such as coal and gas in the grid.

Dr Bjorn Sturmberg flanked by former ANU president and vice-chancellor Brian Schmidt and Federal Labor member for Canberra Alicia Payne. Photo: ANU.

Dr Sturmberg’s PhD centred on solar technology. Before arriving in Canberra, he undertook a project involving solar that he says opened his eyes to the hurdles facing renewable energy.

“We were trying to install solar panels into this apartment building I was living in and it took us 18 months just to get all the regulatory approvals in place,” he says.

“We had to set precedent around the building codes and how they accommodated for lithium-ion batteries, and the building was heritage listed, so there was an extra layer of complexity.

“It’s all these things, human constructs that generally exist for a very good reason, but they’re fit for purpose more for the time they were written rather than the future we’re trying to create.”

Engie EV chargers at the ANU. Photo: James Coleman.

Dr Sturmberg says it’s a smaller version of the same problem his team is trying to solve now.

“When you look at the national grid, how do we get social licence for putting wind farms in certain places and building new transmission lines between states and out to renewable energy zones?

“How do we accommodate electric vehicles, and charging in a way that doesn’t stress the grid? Particularly, when it gets loaded up in the evening time and everyone comes home from work and puts on the heater or air conditioner and does their cooking.

“How can this transition be done one in a way that still meets the needs of essential services?”

He says the proudest moments of his career are when he sees “validation in the real world”, as in recently when 16 Nissan Leaf EVs in the ACT Government fleet plugged into bi-directional chargers fed power back into the national grid during a blackout in Victoria.

“There was a whole different type of satisfaction that came from seeing the data on how the vehicles had actually responded to a real unforeseen grid emergency.”

The Federal Government wants the country running on 82 per cent renewable energy by 2030, which Dr Sturmberg says is a “really good metric”.

“It’s going to take work and an accelerated uptake and deployment of solar and wind and battery storage, but I think it’s also realistic,” he says.

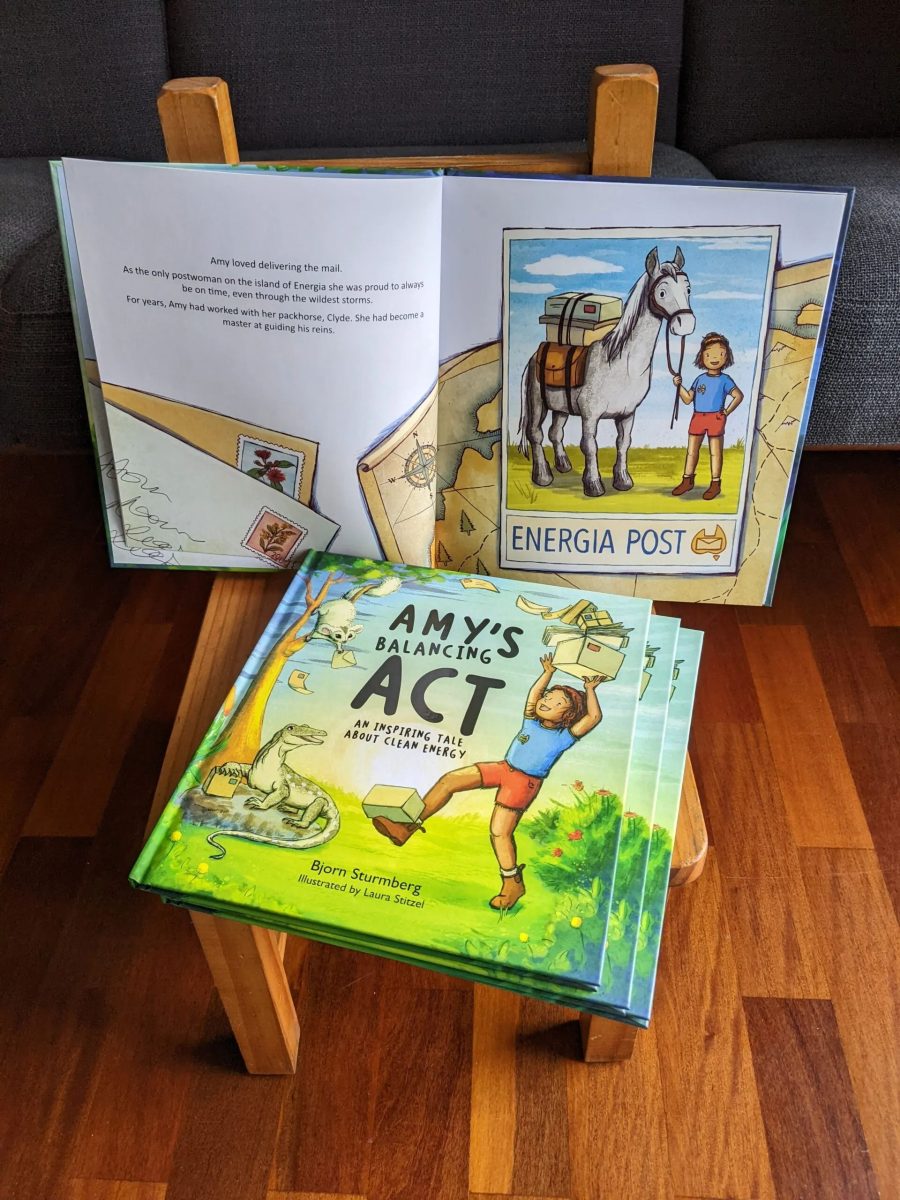

Dr Sturmberg’s children’s book Amy’s Balancing Act. Photo: Dr Bjorn Sturmberg.

“What we really need the most is coherency in the plan for how to get there, in a way that builds social confidence in the energy transition … flowing through to people having the confidence to buy EVs and knowing there will be sufficient charging networks to use them.”

Following in the footsteps of his physics teacher, Dr Sturmberg has published a children’s book. Titled Amy’s Balancing Act, his children’s fable tells of the transition to clean energy, “where different animals represent different energy technologies”.

“There’s a lizard that only has energy when the sun is on its back, or an albatross that can only fly when it’s windy, et cetera.

“It’s trying to show the different aspects of different clean-energy technologies, but also most importantly, how they can work together.”