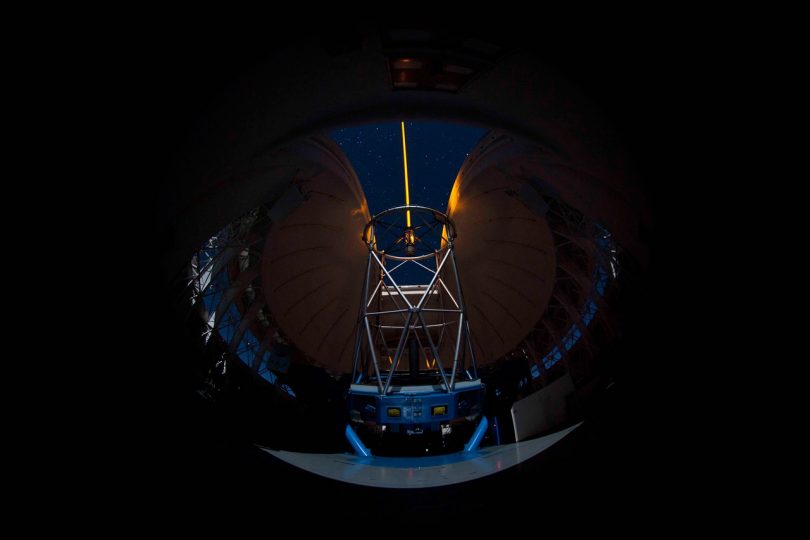

The Gemini South Guidestar Laser (installed by Professor d’Orgeville when working in Chile) seen propagating from behind the second mirror of the Gemini South 8-metre telescope. Photo (take with a fish-eye lens): Gemini Observatory.

A small team of Australian National University scientists located at Mt Stromlo Observatory are working tirelessly to combat the risk to life as we know it, posed by around 500,000 items of space junk orbiting our planet.

While there appears to be no immediate risk to human life and limb, the space junk or ‘debris’ poses a very real threat to our modern forms of communication and everything else that currently happens in space. Think internet, television broadcasting, GPS navigation, monitoring climate, crops, and conflicts … as well as man-made space missions.

It all has overtones of science fiction movies such as Gravity and Armageddon but the answer doesn’t lie in rescue missions into space but in the development of laser technology shot from telescopes and used to move the space debris around to stop it from colliding with satellites and other debris.

Ultimately there is also the potential to move the space junk into a different orbit so that it falls toward earth and is burned up in our atmosphere.

“We want to avoid reaching that point where we can’t use space anymore,” said Associate Professor Céline d’Orgeville, a research scientist at the ANU’s Advanced Instrumentation and Technology Centre, which is part of the Space Environment Research Centre.

“It’s not a solution to clean up space yet but it’s to avoid a catastrophic situation where debris collides more and more.”

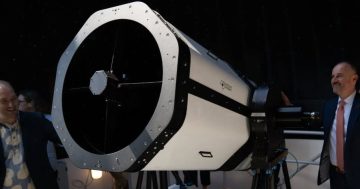

ANU scientist Associate Professor Céline d’Orgeville at work at Mt Stromlo Observatory. Photo: James Walsh, ANU.

Associate Professor d’Orgeville and a core team of around 10 academic scientists and engineers are working on a laser-based research project which uses adaptive optics to gauge the effect of atmospheric turbulence in order to accurately avoid collisions between space debris and satellites.

An orange 20 Watt laser is used to measure atmospheric turbulence above the telescope of the laser tracking station. The tracking station uses another 200 Watt infra-red laser to track where the debris or satellite is in space and where it is travelling to. If a collision is expected, a more powerful 20 kilo-Watt infra-red laser can then be used to manoeuvre the debris out of the way and into a different orbit.

Associate Professor d’Orgeville said her team is hoping to demonstrate how the technology could work on a small scale by the end of 2019, before seeking funding to enable the revolutionary project to operate on a larger scale.

“It would be a really important step towards trying to solve the problem of space debris,” Associate Professor d’Orgeville said.

“It sounds like science fiction but we are really close to it.”

The Gemini South Guidestar Laser seen in action from a neighbouring observatory. The laser was installed by Associate Professor d’Orgeville into an 8-metre telescope in Chile when she worked at the international Gemini Observatory prior to coming to ANU in 2012. Photo: Tim Abbott, NOAO.

Earth’s first piece of space junk was the rocket that carried the Russian satellite Sputnik into space in 1957. Since then it has been added to many times over with old satellites, fragments of other spent space items and the like.

“Space is heavily polluted with objects that are man-made and have gone past their life expectancy,” Associate Professor d’Orgeville said.

She said there are about 500,000 objects of space debris orbiting the earth which are the size of a marble or larger. Around 20,000 of these items are larger than softballs and there are a number of far larger old satellites which have reached the end of their lives.

Associate Professor d’Orgeville said that if things are left to continue then eventually there will be so many collisions with space junk that we won’t be able to continue to use space for man-made missions, new satellites, and everyday space-enabled technology.

“If we lose this capability it would be back to the dark ages,” she said.

Associate Professor d’Orgeville said that once technology is used to prevent collisions, the next step would be to manoeuvre the debris into an orbit which takes it into the earth’s atmosphere where it will then burn up.

Asked about the risk to people if larger items of space debris and satellites fall to earth, Associate Professor d’Orgeville said that this can be controlled and that larger satellites can be brought down into the ocean.

Associate Professor d’Orgeville said that funding and international agreement are the biggest issues in terms of dealing with space debris, as the technology is mostly developed.

To find out more about the research project please go to www.serc.org.au.