Canberra Zoo and Aquarium’s giraffe keeper Sophie Dentrinos talks about the importance of World Giraffe Day as one of her charges, Shaba, opts to devour his lunch. Photos: Sally Hopman.

So what weighs 70 kilos at birth, grows to more than five metres in height (16 feet in the old money) and is not the best patient when it comes to a sore throat?

Yes, it’s a giraffe.

For many of us, they’re that leggy African mammal with a striking blue tongue that just happens to be the tallest animal in the world. But what many people don’t know, according to the giraffe keeper at Canberra’s National Zoo and Aquarium, Sophie Dentrinos, is they are also facing a silent extinction.

“For so long, they have been assumed to be safe, but they’re not,” said Sophie, who has been working with giraffes for 18 years.

“People seem to think they’re safe because they don’t have natural predators. They are rarely trophy animals for hunters, and they don’t have tusks or other body parts that hunters are after.”

So why are they facing extinction?

“It’s us,” Sophie said. “Humans.”

The problem can be linked to the decline in their range – where they can walk or run freely.

“This has declined dramatically in previous decades,” Sophie explained.

Canberra Zoo giraffe keeper Sophie Dentrinos prepares a special treat for her charges on World Giraffe Day.

“The giraffe population has declined by 40 per cent in the last 30 years, with scientists now calling this a silent extinction.

“We are very proud to support organisations such as the Giraffe Conservation Foundation who are doing amazing work to keep our gentle giants around for many years to come.”

On Wednesday (21 June), the Canberra Zoo helped mark World Giraffe Day to raise support, create awareness and shed light on the challenges giraffes face in the wild by showcasing three of its residents – Shaba and Mzungu, both 12, who are the parents of one-year-old calf Themba. Shaba came to Canberra from Mogo Zoo, while Mzungu came from the Taronga Zoo at Dubbo.

Sophie said giraffes had already become extinct in a number of regions in Africa after more than 90 per cent of their habitat was lost.

“What we’re seeing now is that there are fewer areas for them to roam around, so we’re seeing less breeding, less ability to move around and find food.”

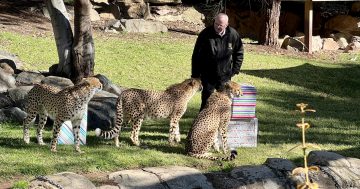

Shaba and Mzungu wander over to greet visitors to the Canberra Zoo on World Giraffe Day.

She said not being able to move around was significant because of the wet and dry season conditions in which they lived, so they were forced to move out of familiar areas and head into places where they came across dangerous obstacles like power lines.

So what can be done to help the giraffes?

Sophie said the Canberra Zoo supported the work done by the Giraffe Conservation Foundation in its translocation projects. It is already part of the accredited international breeding program for giraffes.

Returning animals to the land in which they originally roamed can save their lives – and pull them back from the threat of extinction – but it’s a huge undertaking, often involving governments at different levels, community groups, zoos and wildlife centres and donations from the public. And due to the sensitive nature of animals like giraffes, it doesn’t always work. But experts believe it gives the animal the best chance of a good future.

Although World Giraffe Day has passed, the animals are so special that the Canberra Zoo and Aquarium is extending the celebrations out to this weekend (24 to 25 June) with a number of special giraffe-themed events organised for visitors. They include keeper talks, crafts and, for an extra cost, hand-feeding. More information is available on Canberra Zoo and Aquarium’s Facebook page.