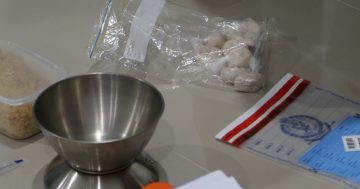

Drug criminalisation does not reduce drug use and often escalates it, according to retired judge Richard Refshauge. Photo: ANU.

A former ACT Supreme Court Justice has called for the decriminalisation of drugs, saying the Territory needs to instead focus on a harm-minimisation strategy as criminal justice policies are not working.

Removing criminal prosecutions for personal use and possession of small amounts of illegal drugs would reframe the use of drugs as a health issue and support vulnerable people in receiving the help they need, retired Justice Richard Refshauge said.

“Decriminalisation is really important because the harm that drugs do is magnified by the involvement of small-time users in the criminal justice system for two reasons,” he said.

“One is it ultimately does not reduce drug use and often escalates it, but also it brings people who have not breached major social norms into situations which make it more difficult for them to participate in the community.

“Having a criminal conviction can prevent a person from securing employment, cause relationship breakdowns, and even lead to poverty and homelessness.”

Being trapped in the criminal justice system can lead to users reoffending and costs significant taxpayer dollars to go through the courts and jail the offender, says Directions Health CEO Bronwyn Hendry.

“All the evidence tells us that criminal penalties do not reduce drug use, yet two-thirds of Commonwealth Government drug strategy funding is spent on law enforcement,” she says.

“Currently only a small portion of people with problematic drug use receive the assistance they need.

“Importantly, the person would not have a criminal record simply for personal use or possession of small quantities of illegal substances that will impact their ability to gain employment or participate in other community activities.”

Despite Australia’s National Drug Strategy having three pillars of harm minimisation, 66 per cent of funds that are allocated to respond to illegal drugs is spent on the first pillar of supply reduction. Treatment programs receive 32 per cent of the budget while the third pillar – harm reduction – receives only 2 per cent.

The Directions Health position paper says that a health-first approach would still impose penalties for drug use, but would ultimately reduce the cost to taxpayers by keeping the offender out of the criminal justice system.

“Civil or administrative sanctions, such as a fine or other conditions, may still be imposed, and any illicit drugs found by police confiscated,” the paper says.

Decriminalisation has the potential to reduce crime rates by providing an opportunity to intervene before a person’s drug use becomes more serious.

Ms Hendry says incarceration rates for illicit drug offences have increased over the last decade by 64 per cent.

“Australia has the highest rate of policing drug use in the world. In the last 12 months, 81 per cent of drug offences were for personal use, not supply,” she says.

“Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and other disadvantaged populations are disproportionately represented.

“Australia needs to introduce a holistic, harm-minimisation based approach in order to have a chance at decreasing our high rates of incarceration and overdose deaths.”

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, drug deaths hit a 20-year peak of 1,808 deaths in 2016, falling slightly to 1,740 in 2018, of which 1,123 were opioid-related.

While opponents of decriminalisation often point to the fact that users know the consequences of engaging in illegal activities, Justice Refshauge told Region Media that laws need to serve a social purpose, and the current laws are simply not working.

“What we know is that at the moment making drugs illegal enhances and exaggerates the harm drugs do,” he said. “A good example is Prohibition in the United States. What happened was it didn’t reduce the consumption of alcohol but did all sorts of other bad things.

“In other instances, you can show a relationship between the breaches of the law and the criminalisation of those incidents in reducing breaches. We all know if you get a speeding fine it makes you drive more slowly but with drugs, the process is much different.

“The evidence from 23 countries around the world where decriminalisation is now in play is that it reduces incidents of drug use and increases the rehabilitation of addicts.”

Portugal decriminalised all drugs in 2001 as high rates of heroin use plagued the country and ended up seeing a 60 per cent increase in people seeking treatment, as well as drug use go down in almost every category.

To achieve similar results, Directions Health says the government can either pass new legislation or encourage police and law enforcement to use discretion and stop those caught with small amounts of drugs from being ushered into the criminal justice system.

The paper also stresses that manufacturing, distribution and the sale of illicit substances would still remain a criminal offence under a decriminalisation approach.