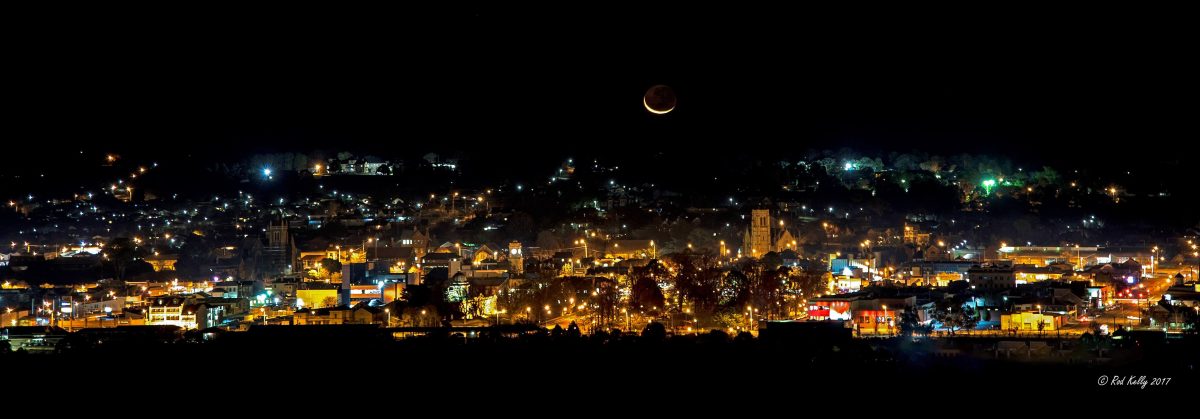

A glittering skyline greets a multitude of tiny bats that are living in Goulburn, feeding off insects drawn to the lights. Photo: Rod Kelly.

People living with colonies of tiny bats are unlikely to know they are sharing their home with these native creatures of the night.

Weighing between six and 10 grams, more of these insect-eating bats are coming into urban areas to reside in our attics, chimneys, wall cavities, backyard sheds and large gum trees.

Because they wait until the depths of darkness to venture outside, most of us are tucked up in bed unaware of our home’s shadowy secrets says Heather Caulfield, who rescues bats.

“There are some species that are quite comfortable living near humans because they have worked out the lights on in the houses or verandahs attract insects,” she said. “Some species will set up their roost really close to the light over the front door so they know they can virtually have breakfast in bed.”

Lesser long-eared bats are some of the most common to be rescued from houses in the Southern Tablelands, living in groups of about 12. Another species, the little Forest Bat weighing no more than 6 grams, looks as big as swallows darting around at dusk.

“Within a colony there will be a group of female best friends; they spend all their life hanging out together,” Heather said. “They go out and get pregnant on the same night together. They pretty much give birth within a day or two of each other and just spend all their time hanging together.”

If people do discover bats in their home, they are best left alone, according to Heather.

She said wildlife rescuers could not just remove bats. “They have to be released within a very close area and the bats will go straight back in there (to a home) if you don’t seal it up anyway,” Heather said.

“If you can jam your thumbnail into something a bat will get through it,” she said. “Few places could be renovated sufficiently to get rid of every thumbnail-sized gap. The odds are they’ll come back in.”

A white-striped freetail bat. Weighing about 30-47 g, this is one of the largest insectivorous bats found in NSW, which can fly swiftly, around 60-65 km/h. Heather has rescued these from farmlands around Tarago and Crookwell. Photo: Heather Caulfield.

Roosting in homes, bats don’t chew wires or wood or bring in nesting material. “They eat up to their own body weight in insects every night when they are being active,” Heather said. “If you want to think about them eating mosquitoes, it’s a really handy thing to have around your house.”

Heather said people’s main health concern with these natives is the Australian bat lyssavirus. “If you never touch a bat you never have to worry about the Australian bat lyssavirus. That is only passed through saliva if you picked up or touched a bat and it bit or scratched you.”

Heather is constantly removing bats from people’s homes. “Cats are one of the biggest issues, they bring bats inside,” she said.

“Sometimes they wedge themselves in tight behind picture frames or in doorways or sliding doors,” she said.

She has released bats that have come in from houses around Victoria Park in Goulburn, a haven for bats because of the large gum trees.

“I had a rescue in Crookwell for a bat that had got its wrist caught in a window flyscreen. There had been a little gap there and it had its wrist caught in there and could not get away.”

People should expect more bats and flying foxes moving into urban areas this summer, driven by extreme heat, fierce storms and loss of habitat. Centuries old towering gum trees with hollows are being pulled down for housing developments, land clearing, mines and quarries, leaving bats homeless.

Consequently, wildlife rescuers like Heather, who has the only purpose-built bat aviary in NSW at Windellama, are seeing a dramatic change in rescues.

About 80 bats came out of one branch that fell about 20 metres to the ground last year. The species was the vulnerable white-striped freetail bat. Another mass rescue was triggered when 178 bats came into care from one location where a house was being renovated.

All the adults that could fly left, leaving pups to be farmed out to carers across NSW. Caring for them involved a massive effort because the pups needed four-hourly feeds.

Caring for many bats over time Heather Caulfield has become invested in their survival. Photo: Supplied.

Eventually, all these bats came into Heather’s aviary.

“They need to learn to fly, they need to learn to hunt, to forage,” she said. “In the wild they would have time to learn with their mother before they are weaned.”

Working with a network of WIRES volunteers Heather is keeping many little bats circulating and eating their weight each night in insects, and adding to biodiversity.

Original Article published by John Thistleton on About Regional.