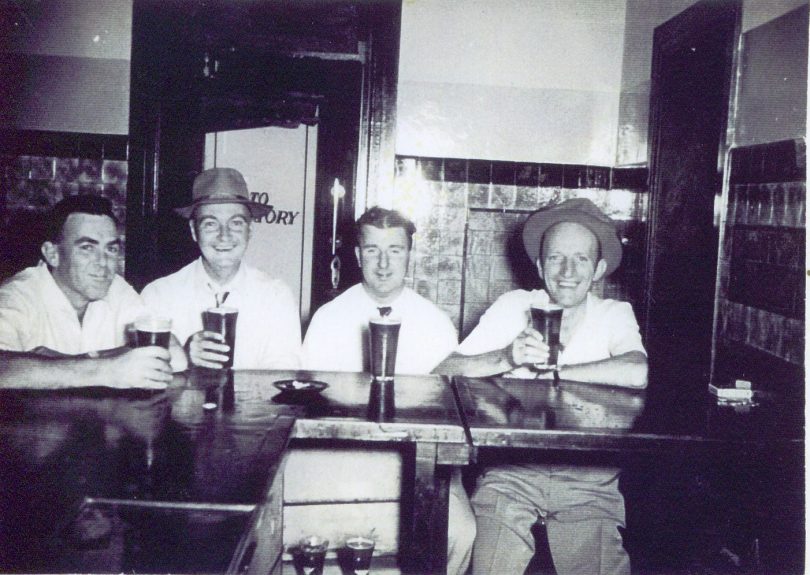

The Maher Cup once was the talk of the town, and a hot topic in the pub. Here, Jack Coulton, Ray Dunn, Vince Sullivan and Gordon Hardwick share a beer at the Royal Hotel, Gundagai about 1950. Photo: Lost Gundagai Facebook page.

A famous bush football competition that flourished after the Great War for 50 years then disappeared is returning – at least in book form.

A Group Nine, Saturday afternoon contest, the Maher Cup ignites rugby league full-throated fanaticism among anyone who played or followed the game until the early 1970s. Recently at Tumut, where the late Ted Maher launched the cup when he was the local publican, a reunion game saw the local Blues team thump their close rivals the Gundagai Tigers by 30-12. So perhaps, it will return in all its glory.

Among the big crowd of onlookers was Neil Pollock, who has over the years created a comprehensive blog, The Maher Cup, that will be published into a book later this year, The Maher Cup – a social history of football in the Group Nine towns 1920-1971. Packed with descriptions of all 729 games played in the original competition, this book promises to match country newspapers from the letterpress era as the game’s bush bible. Extraordinary stories of trains loaded with 1000 supporters rattle through the pages alongside fisticuffs, protests, flooded ovals, near riots and staggering betting.

The cup spread rapidly from Tumut to Gundagai, Boorowa, Harden-Murrumburrah, Young, Grenfell, Cowra, Cootamundra, Gundagai, Junee, Temora, West Wyalong and Barmedman. Railway branch lines snaking over flat wheat country carried crowds from town to town. Back then, communities of roughly the same size were fierce competitors.

Keen to put the horrors of war behind them, many of the players and home-town followers were Irish Catholic farmers and labourers. Local newspapers fuelled rivalries, creating hysteria over the cup. In the 1950s, Sydney coaches steamed into Group Nine raising the standard of football.

Pollock says he could not have gathered his rip-tearing stories without three generations of Sullivans who produced the Gundagai Independent.

“They were not proper journalists, they were all poetic writers, they loved a simile, you would have footballers running on to the ground as Greek gods,” Pollock says.

Here’s a taste from Pat ‘Scoop’ Sullivan in his 2001 cup reunion speech:

“Football not only inspired fanaticism, tears and violence, it also led some people to prayer. I remember when one of our hosts tonight, John Madigan had his rosary beads out, spitting out Hail Marys at machine gun speed, as Harden took an after-the-bell penalty for a win. The power of prayer did not prevail on that occasion.”

Rusty Gorham with the Cup and the Lord. Maher Cup historian Neil Pollock, who provided the photo, says it is his favourite. Photo: Rusty Gorham.

Pollock says the Independent’s circulation outstripped the population of the town because people outside Gundagai became hooked on its in-depth Group Nine coverage and much-loved style.

Like this from 1952: “The Gundagai backline – usually considered a crackerjack combination – were as dreary and listless as a mob of rabbits with myxomatosis.”

“Gundagai is a fascinating place,” says Pollock. “They hate bigger places, and being almost socially isolated people thought, we are special and liked looking after one another.”

But Pollock hasn’t allowed himself to be carried away by the cup’s drama.

“So much of it was hyperbole, the true story is more mundane than mythology,” he says.

Still, a compelling story of organisation and administration emerges. He believes the arrival of cars helped end the railway’s golden run, and with it the Maher Cup. The growth of Wagga Wagga and Canberra sucked the life out of the smaller communities who had nurtured their cup legends. Where pubs once served thirsty wheat farmers and their lumpers, agribusiness companies have taken over, and the colour and characters have shrivelled.

Pollock’s father Ted was a friend of international Ron ‘Dookie’ Crowe. “Ron and his brother Les were timber cutters and carriers. They used to supply farmers with strainer posts. I remember Dad pointing proudly to a post he had just put into place. ‘You know, that post is like Dookie, it’s just a bit bigger, stronger and tougher than your average post’.”

Separate from Pollock’s blog, Harden-Murrumburrah stalwarts remember legendary halfback Nick Cullen, who played 400 first grade games, and halfback Eric Kuhn who coached and inspired his successor Jack Whybrow. The son of a woodcarter, Whybrow could drop big forwards with devastating tackles and played alongside wool classer and NSW Country’s stylish five-eighth John Shea in two cup games in the early 1970s. “We beat Barmedman, then Young took the Maher Cup off us in the next game, it only went for a few more games and it was all finished,” Whybrow says.

But the cup lives on in folklore … and the memories of the region.