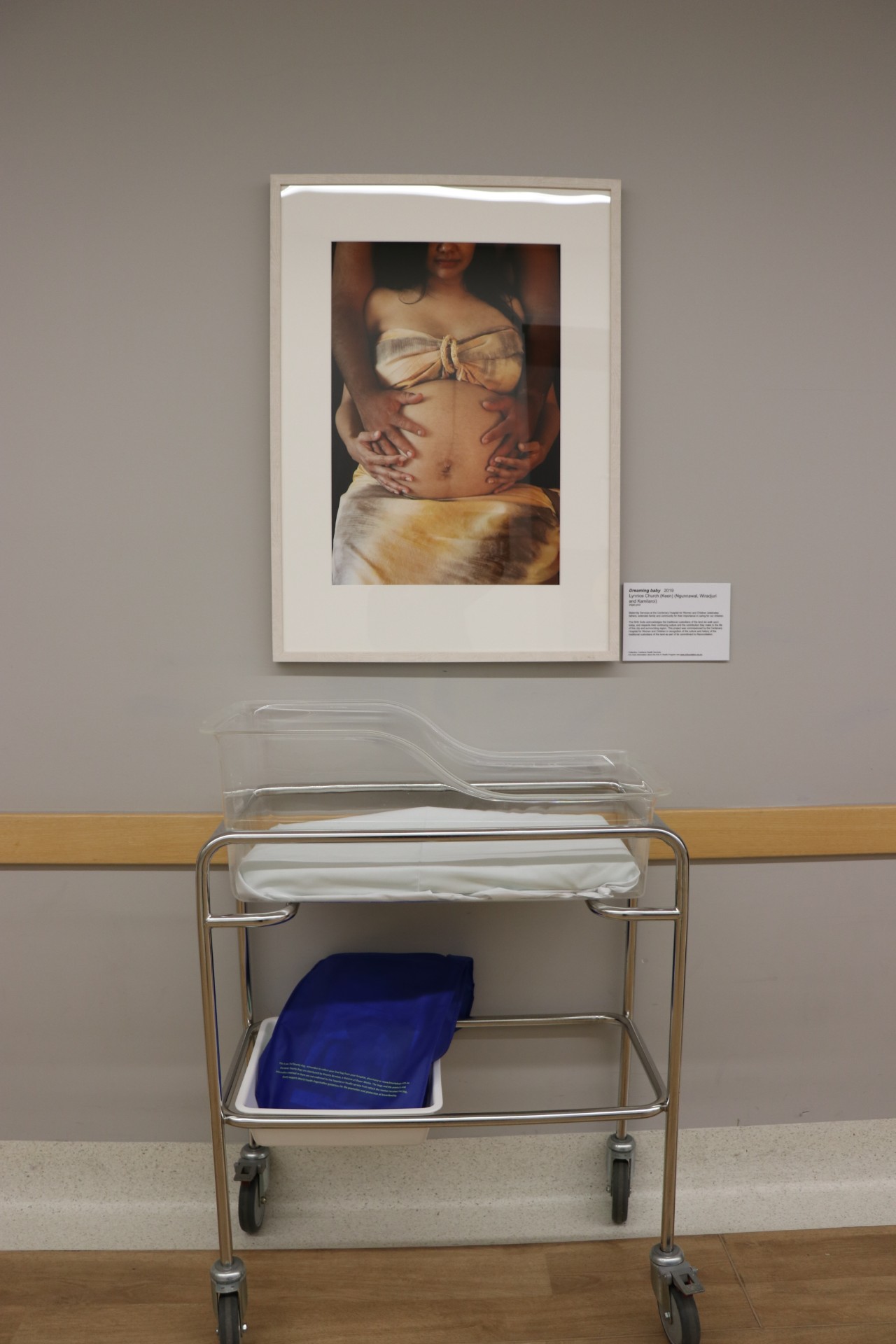

Art work by Lynnice Church. Photos: Supplied.

When we think about finding works by Canberra’s internationally renowned visual artists, as well as emerging artists, The Canberra Hospital may not spring to mind.

But with the support of the Canberra Hospital Foundation, an Arts in Health program is providing connections between people in the hospital and their local community.

Dr Jenny McFarlane is the part-time Arts in Health curator at Canberra Health Services. Dr McFarlane talks to staff, consumer representatives and carers about what they want to communicate to people in specific areas in the hospital, and who they want to communicate with. For example, recent artwork added to the maternity areas in the Centenary Hospital for Women and Children needed to create feelings of inclusion and welcome.

Infection control is a limitation on the kinds of artwork that are suitable for the hospital environment.

“We don’t want art that people want to touch and then touch their mouths, that sort of thing,” Dr McFarlane said. But there are other logistics concerns about where works are placed and what is suitable for a space. “Birth Centre is a perfect example where there is no natural light, so they’re perfect for works on paper,” she said.

Building community is a common theme to be communicated, so Jenny looks for artists that are familiar with the Canberra community. Often, their work includes references to recognisable people or places. An example is popular series of works by Trevor Dickinson hanging in a hospital corridor, featuring the Manuka Pool diving tower, a bus shelter and the Mandalay bus.

Canberra landmarks by Trevor Dicksinson. The diving tower at Manuka Pool and the Sunrise drive-in sign.

Feeling at home in the hospital has a direct impact on a person’s healing. “That sense of identity, seeing your place represented on a wall and made to look as good as it does, there’s something about that that makes you feel at home. If you feel as if you’re in the right place, if you feel as if you’re at home, you feel empowered to ask questions,” Dr McFarlane said.

Five artworks by Trevor Dickinson hanging in a hospital corridor near the entry to Building 10.

What people need from an artwork is what makes the hospital experience of art different from seeing the same work in an art gallery, and is why some artworks are not suitable for the hospital.

Dr McFarlane contrasts going to a gallery, where the person has chosen to experience artwork that may raise confronting ideas or traumatic experiences and feels prepared for the experience, with a hospital where the person has not made a choice to experience art and is probably already having a very difficult experience.

“You want something that you can lose yourself in, that you can re-centre yourself with, that is going to remind you of better times or good times to come or that you are surrounded by a community of people that care about you, that you are part of a larger positive community,” Dr McFarlane said. “But you also need uplifting and positive and joy. Those emotions are really important, too.”

Artwork by Judy Horacek.

An example of a work in the hospital that creates some of these positive feelings is Lynnice Church’s photograph in the Centenary Hospital for Women and Children’s maternity area. As a woman with Ngunnawal heritage, Ms Church wanted to celebrate the role of Aboriginal fathers. Her work shows the mother embracing the father, and the father embracing the soon-to-be-born baby. “It’s stunning … it’s calm, it’s full of positive energy and expectation, but it’s also an image of embrace and love,” Dr McFarlane said.

For the future of the program, Dr McFarlane is interested in including the creation of art in the hospital environment as well as participating in art as viewers, and in arts beyond visual works such as poetry, music and theatre.

Dr McFarlane referenced research being done by Dr Hilary Moss, former Director of the National Centre for Arts and Health at Tallaght Hospital and now teaching at Trinity College in Dublin.

“She talks about the difference between a receptive experience of art, and an active experience of art. You’ve come into the hospital typically and you’ve got other things on your plate, and you want to experience art as a receiver of art, not a creator. But there are other environments in hospital, particularly rehabilitation, where you need that distraction of being able to make something, do something. A controlled experience of art that’s safe and supported … so the experience is not just about that wound or that condition, it’s about who you are as a person,” Dr McFarlane said.