Yalata elder Mima Smart, OAM tells her story in Maralinga Tjarutja to be screened at the NFSA on 13 July, including a Q&A with filmmaker Larissa Behrendt. Photo: NFSA.

Many stories have been told about the Maralinga tests in 1956, but perhaps not the most important one.

It’s more than the story of how the British conducted its first nuclear tests on the South Australian site. Rather, according to filmmaker, broadcaster, academic and lawyer, Professor Larissa Behrendt, AO, it’s the story of dispossession, of disruption to life and of removal of lands.

A Euahleyai/Gamillaroi woman, Ms Behrendt, who wrote and directed the film Maralinga Tjarutja, will talk about the stories behind it, from the people who were there and those whom it affected, at a special event at the National Film and Sound Archive (NFSA) in Canberra on 13 July.

When approached in 2020 to make the film, Ms Behrendt said it was of paramount importance it be about how the traditional owners of the land wanted their stories to be told – “not necessarily how I wanted it to be told”.

Maralinga Tjarutja, now an award-winning documentary, shows the tenacity of the Maralinga people, whose connection with that country goes back 60,000 years. It’s about their fight for the clean-up of radioactive and other contamination, for compensation and for the handing back of the Maralinga village and test sites in 2009.

On 27 September, 1956, Britain, with the permission of then Australian Prime Minister Robert Menzies, conducted its first atomic test at Maralinga. Radioactive fallout blown by the wind was detected as far away as Townsville in North Queensland.

No British officials paid any consideration to the traditional owners of the land, the Anangu Pitjantjatjara people. Only the patrol officer attached to the test range, Walter MacDougall, a missionary, voiced his concerns.

Chief Commonwealth scientist Alan Butement wrote in a letter to Mr MacDougall’s manager: “Your memorandum discloses a lamentable lack of balance in Mr MacDougall’s outlook, in that he is apparently placing the affairs of a handful of natives above those of the British Commonwealth of Nations.”

Ms Behrendt said the story had to be shaped by community consultation.

“It was also not just about one disaster, it was about three. First, when the railroad came through, then the closing of the Ooldea waterhole and mission on the edge of their country – and then the testing.

“There had been other stories about the impact of testing, but not their stories.”

Ms Behrendt, who hosts the Speaking Out program on ABC Radio, said making the film also illustrated the importance of story-telling and making sure such experiences were recorded for future generations.

While researching Maralinga Tjarutja, she travelled with community members to the South Australian Museum.

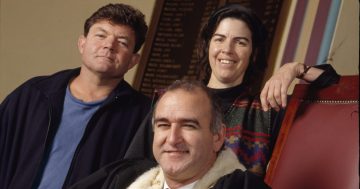

Filmmaker Larissa Behrendt will be at the NFSA on 13 July for a Q&A about her film, Maralinga Tjarutja. Photo: Supplied.

“They had lots of photographs from the mission,” she said. “They gave me copies of them to take back to the community. It was a lovely piece of repatriation because the community didn’t know what the museum had.”

Because such important archival material had been discovered during the film’s research process, she said its screening at the NFSA was meaningful.

Ms Behrendt said she saw her filmmaking role as providing a platform for people to tell their stories – most of which had a strong political message.

“I prefer to stay behind the scenes,” she said, “it’s important to give people space to tell their own stories.”

She said the question most asked at her Q&As is about her transition from lawyer to filmmaker, although she maintains a law practice in Sydney.

“I see them as an extension of the same thing. I became a lawyer because I wanted to change the world.

“I grew up in a politically aware household, both my parents had a strong sense of social justice.

“Moving from the law to academia, I felt academia could give me more of a basis to work on reform.”

Now a distinguished professor, Ms Behrendt is the Laureate Fellow at the Jumbunna Indigenous House of Learning at the University of Technology, Sydney.

The Maralinga Tjarutja screening and Q&A with Larissa Behrendt is on Saturday 13 July at 1 pm at the Arc Cinema, National Film and Sound Archive, Canberra. Bookings essential.