A survivor of Cameron Flynn Tully has come forward to tell her story. Photo: File.

Content warning: this story includes details of childhood sexual abuse.

When Alice* was about 10 years old, she was just a normal kid, maybe a little on the shy side. Then notorious paedophile Cameron Flynn Tully brought his darkness into her life.

In 2014, a jury found Tully guilty of 18 charges against eight children.

The ACT Supreme Court’s Justice John Burns said most of Tully’s crimes took place at his family’s rural property Hillview, near the north Canberra suburb of Cook, where his mother ran support groups and church meetings and where he supervised younger children.

Alice, who believes she was the first of these eight victims to speak out, endured a frustrating lack of support as his case travelled through the justice system before speaking to the media for the first time years later.

“I’m still a normal person. I’m a little bit shy,” Alice told Region Media.

“I don’t think what he did broke or changed me. It’s painful to think about, but most of the time, I don’t think about it.

“For the last seven years, I haven’t worried about it. I’ve just lived. It’s only been in the last 12 months that it’s been shoved back in my face.”

This is because, having spent a little over seven-and-a-half years in jail, the now 47-year-old Tully has been approved to be released on parole.

It’s brought back memories Alice wished she didn’t have.

It was 2011 and Alice was in her mid-20s when she first decided to speak out for the sake of a friend, who is also numbered among the survivors.

“I spent a long time pretending it didn’t happen,” she said.

“[My friend] really struggled with what happened to her. She had talked to me about going to the police a number of times.

“I guess the best way I could support her through that was to go through it as well, so I did it for her.”

Alice recalled how a woman both she and Tully knew initially refused to believe her story, until this woman heard a person close to her had also been violated.

“If you know Cameron, you understand how he can wrap you up in a lie,” Alice said.

“He’s very smart, very charismatic and very manipulative.”

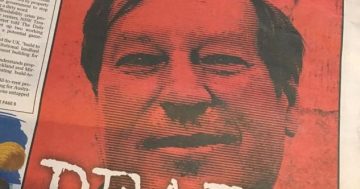

Cameron Flynn Tully was jailed for sex crimes against eight children. Photo: Supplied.

When the case reached the courts, she struggled to get authorities to give her information on any developments, ringing every time the case was mentioned in court and being told nothing happened.

“All I could get of what was happening was through the newspapers,” she said.

“I drove all the communication during that time. I find that really frustrating.”

Once a trial date was set, she was helped by an “amazing” witness assistant and went on to testify against Tully while also looking after her seven-week-old son. But she felt strange once the jury came back with guilty verdicts.

“It’s a weird feeling because I guess you’re celebrating, but you’re not,” she said.

That same year as the trial, 2014, Justice Burns sentenced Tully to 14-and-a-half years’ jail with a non-parole period of nine years.

But in 2016, this was, in part, successfully appealed on a technicality.

The ACT Court of Appeal said Alice was a “truthful witness” and the jury must have been satisfied beyond reasonable doubt Tully did act the way she had alleged. However, it found there was insufficient evidence to prove it had happened before she turned 10, which was required by the type of charges laid for her case.

As a result, the court entered not guilty verdicts for the four charges in which she was the complainant, and Tully was resentenced to a seven-year-three-month non-parole period.

“It was a big kick in the guts,” Alice said.

“I don’t understand how you can assault eight people and spend seven-and-a-half years in prison, and that’s okay, that’s enough. It’s not even a year per person.

“I want him to be famous for the disgusting person he is.”

After the appeal process started, she had to deal with a lack of communication from authorities again, spending months ringing to learn more but being told nothing.

She said the first she heard there was an outcome for the appeal was when she was having coffee with a friend and a Google alert for Tully’s name popped up on her friend’s phone to say there had been a result.

Furious, Alice called the ACT Director of Public Prosecutions and claims she was told: “‘Something had fallen through the cracks’, which just made me so f-king angry, because it wasn’t ‘something’, it was me.”

“It was me and seven other people that they let fall through the cracks.

“They had so much time to notify us and just didn’t. You can’t tell me it takes longer for a reporter to write an article than it does to make a phone call.”

Alice keeps in contact with one of her fellow survivors, who told her “the level of anxiety and anger is pretty unbearable”.

Alice no longer talks to her first friend, the person who was the reason she went to the police, as “she blamed me for being assaulted because I didn’t come forward early enough”.

What will Alice do now?

“Just carry on. Just live,” she said.

ACT Policing said it was disappointed a survivor was not happy with the support provided by police and other parties during Tully’s prosecution, and there was a well-established complaints management system that could be accessed if anyone had concerns about the actions of police.

“ACT Policing officers endeavour to ensure victims, witnesses and other interested parties are kept up to date on court proceedings and outcomes throughout the judicial process,” a spokesperson said.

A spokesperson from the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions said victim engagement was a very high priority.

They said that the DPP had strengthened its internal Witness Assistance Service over the past five years and its engagement with the Victims of Crime Commissioner to ensure its victim engagement was of the highest possible standard.

*Not her real name.

If this story has raised any concerns for you, 1800RESPECT, the national 24-hour sexual assault, family and domestic violence counselling line, can be contacted on 1800 737 732. Help and support are also available through The Canberra Rape Crisis Centre 02 6247 2525, The Domestic Violence Crisis Service ACT 02 6280 0900, Lifeline 13 11 14, the Suicide Call Back Service 1300 659 467 and Kids Helpline 1800 551 800. In an emergency call 000.