Ralph Heimans’ portrait of Prince Charles is filled with myriad symbols of his life. Photo: National Portrait Gallery.

In a huge and striking painting, a man stands by a window, bathed in a wonderful radiance. His features are familiar. It is King Charles III, not shown in formal regalia but in a casual suit, caught in a pensive moment.

The Prince of Wales, as he then was, was painted in 2017 by Ralph Heimans. The portrait is set in Dumfries House in Ayrshire, Scotland. Dumfries House is an 18th-century Palladian villa with one of the most important collections of Georgian Scottish and English furniture in the UK. The Prince’s Foundation helped to save the house for the nation.

The painting is dominated by two compositional features: on our right, an arcaded corridor that plunges perspectivally dramatically into depth, and on our left, a majestic spreading oak tree growing outside the window. The polished lid of the grand piano positioned in front of Charles reflects the oak tree, so nature seems to enter the house.

Symbolically, the compositional elements may allude to Charles’ passions – the environment, the preservation of cultural heritage and man’s harmonious coexistence with nature.

Charles is at the centre of the composition, around which everything revolves. The carpet at his feet, the exquisite parquetry floor, the fluted column, and the orrery—the mechanical model of the solar system—are located behind the sitter.

Within this symphony of harmony, we notice that Charles holds a walking staff – possibly a reference to human frailty.

If one pauses to examine the painting, one realises that Heimans’ portraits are more than an exercise in capturing an exact likeness; rather, they set out to weave a narrative—to tell a story about the sitter.

Ralph Heimans is not a household name in Australian art circles; in fact, few outside those specialising in portraiture would have ever heard of him.

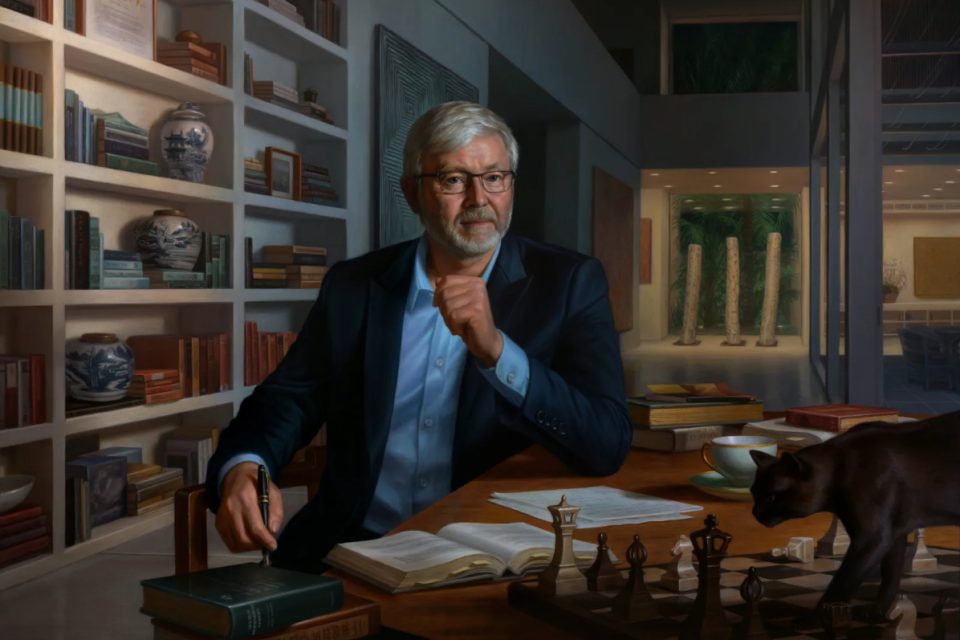

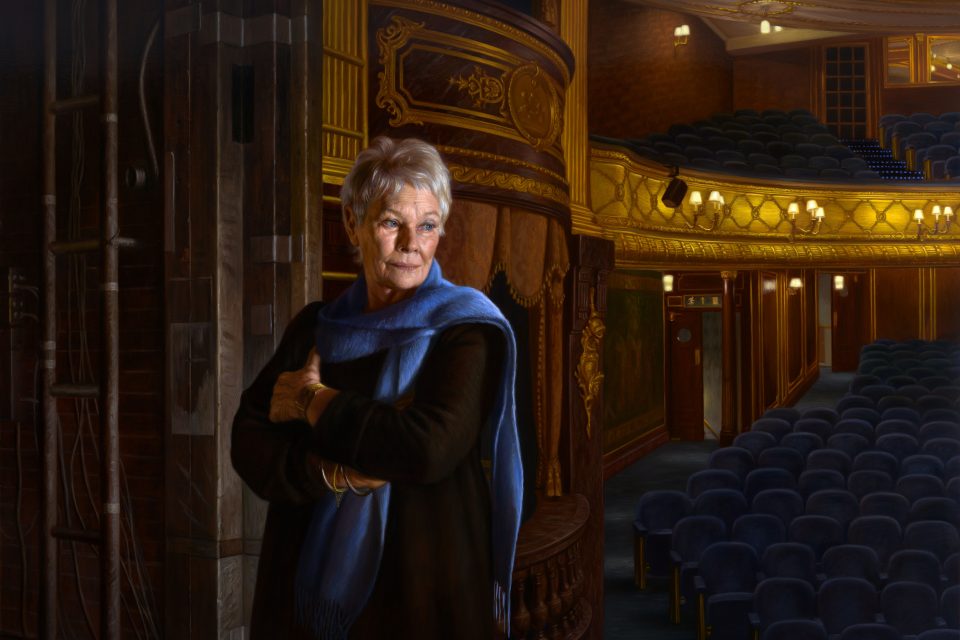

This is despite the fact that he is a Sydney-born artist who has painted some of the most recognisable figures in modern history. His paintings have included the huge portrait of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II for Westminster Abbey, HRH Crown Prince Mary of Denmark for the Danish Museum of National History, Dame Judi Dench, Vladimir Ashkenazy, Kevin Rudd, Dame Quentin Bryce, Michael Kirby and many others.

Heimans’ portraits are generally large, painted over many months, sometimes years, and are inevitably commissioned. After they are finished, they are tucked away in collections around the world.

This exhibition is a unique opportunity to see so many Heimans portraits assembled in the one place, for which the National Portrait Gallery needs to be congratulated.

The artist himself is seeing some of these portraits for the first time in many years and, as never before, assembled in an exhibition. We are seeing possibly about a quarter of the artist’s portraits painted to date.

Heimans is essentially a self-taught artist. Born in Sydney in 1970 to a Dutch Jewish father and a Lebanese mother, he took drawing classes at Julian Ashtons and some private classes with a Polish academic painter, Zbigniew Dromirecki.

At Sydney University, he started his studies in architecture and then quickly gravitated to art history and pure mathematics. The rest he learnt by studying the work of the great masters in museums throughout Europe. Today, he divides his time between Sydney and London.

Heimans has developed a distinctive language in his portraiture – you can tell that it is one of his portraits from 20 paces. He is a very deliberate painter, with portraits planned to the last detail before he commences the piece.

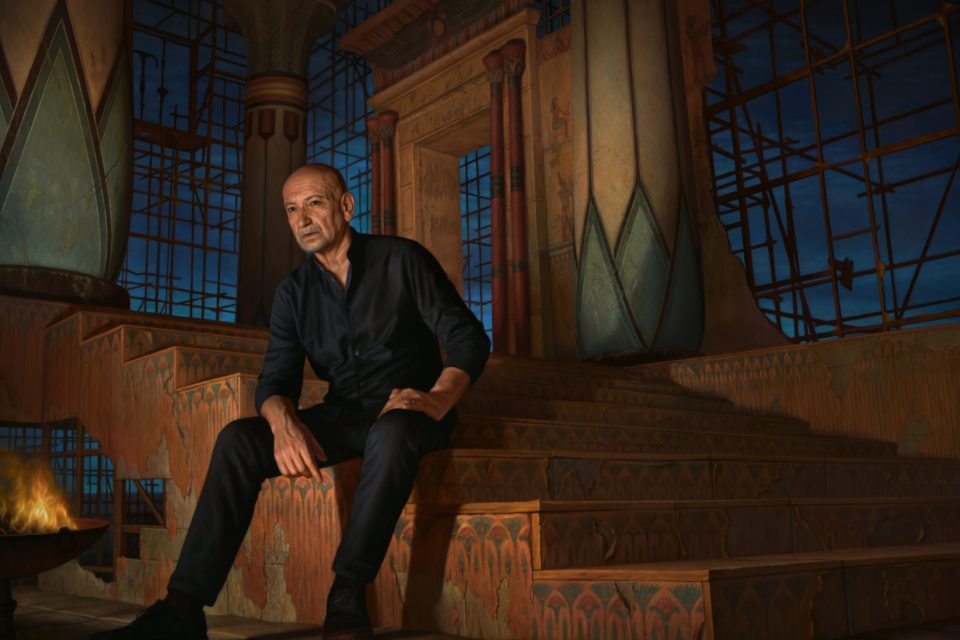

He paints what may be termed ‘narrative portraits’. In other words, instead of a head and shoulders or a full-length portrait cast against a neutral background, he engages his sitter in a particular setting, whether it be Ashkenazy within the internal structures of the Sydney Opera House, or Queen Elizabeth II symbolically revisiting the place of her coronation at Westminster Abbey for her Diamond Jubilee.

Heimans’ passion for mathematics finds reflection in the plunging perspectival structures that his figures inhabit. The spaces are symbolically charged and full of clever inventions with attributes, reflections, mysterious shadows and countless references to art history.

They are thinking pictures that go beyond the initial ‘wow’ factor and invite the viewer to contemplate the world of the sitter bathed in a mysterious light that hints at other realities.

Ralph Heimans: Portraiture. Power. Influence is a memorable exhibition that, for many people, will serve as an introduction to the work of this remarkable artist.

In the 1st century BC, Horace wrote about portraiture: “In painting, he shows both the face and the mind.” This aptly describes what Heimans sets out to do in his portraits.

Ralph Heimans: Portraiture. Power. Influence is at the National Portrait Gallery until 27 May, daily from 10 am to 5 pm. Charges apply.

Sasha Grishin is an arts critic and writer.