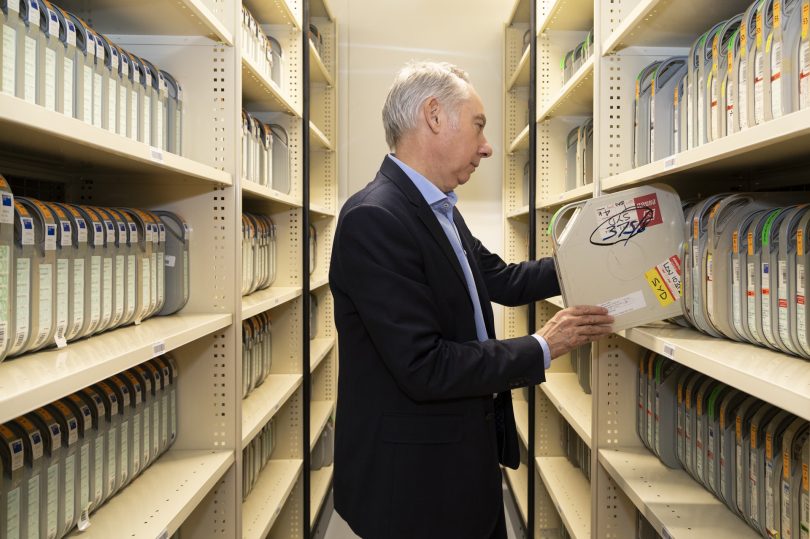

The National Archives of Australia are racing against the clock to digitise and back up millions of documents and hours of magnetic tape before 2025. Photo: Michelle Kroll.

Thousands of tapes and recordings from Australia’s history and the national record could be lost within the next five years because of a lack of resourcing and staff at the National Archives of Australia (NAA), according to the Assistant Director-General of Collection Management, Steven Fox.

He said there are more than 220,000 hours of tapes and millions of pages of archival documents – including 850,000 World War II service records – that need to be digitised before 2025, which is when the NAA will face a losing battle to preserve these records.

Dr Ben Gascoigne at work at the Mount Stromlo Observatory in Canberra, 1948.

NAA: A1200, L11508 pic.twitter.com/oxt0JzoUQb

— National Archives of Australia (@naagovau) June 25, 2020

“One of the great challenges with a lot of that magnetic tape is that there is no quick way of doing it. Every hour of tape takes at least an hour to digitise,” Mr Fox told Region Media.

“Given that we do not have endless resources, that is the great challenge [ahead of] the 2025 deadline, which is the point where technical obsolescence hits home with all the magnetic tape.

“That is the date that was agreed where the age of the skills that are in the workforce and when the equipment – none of which is being manufactured now – lasts until.”

Most of the tapes held at the National Archives storage facilities are broadcasts from the 1970s, 80s and 90s, but some date from the 50s. They cover everything from state election reporting, Commonwealth Games coverage and ANZAC Day marches to documentaries, grand finals, state sports leagues and even Countdown episodes.

A woman tries on a hat at a millinery shop in Canberra's Civic Centre, 1963.

NAA: A1200, L44055 pic.twitter.com/8aWu1yknZA

— National Archives of Australia (@naagovau) June 26, 2020

There are also tapes from events that may not have seen the light of day in decades, if at all, such as Government Committee hearings and communications from within Government agencies.

All of it will be made publically available and will help form a more complete picture of Australia’s history and development.

Mr Fox said the importance of these artefacts became evident when the Palace letters were released and Australians gained greater insight into our political history 45 years after the fact.

“There is definitely classified material, but by the time it is made public it is unclassified or we go through a process of assessing it to determine if it can be fully opened or open with exemptions,” he said.

“But there is a backlog. In broad figures, we get 40,000 requests, and we can process 20,000 of them. We are not saying give us more money, there is a pandemic on for God’s sake – we have to be realistic and pragmatic about it.”

However, Mr Fox put the figure at $20 million to tackle the entire magnetic tape collection by 2025 and get to a point where the NAA would be comfortable saying they have done a proper assessment and will not lose any of that material.

“It does not have to necessarily be resourced in-house, but the more fragile material, the more tricky material, we have some great skills in-house that have worked with [half-inch tape] for a long time and know its peculiarities,” Mr Fox said.

For more information, visit the National Archives of Australia.

Assistant Director-General of Collection Management Steven Fox says the NAA will face a losing battle to digitise records from 2025. Photo: Michelle Kroll.