Fitzgerald’s Canberra: A Guide to Life in the National Capital – the real story of Canberra in the 1960s, read on if you dare. Photo: Sally Hopman.

We all have memories of Canberra, regardless of our vintage. But it seems the further back you go, the better the stories – possibly because you can elaborate and no one remembers what really happened.

That is, of course, unless you were a bloke called Alan Fitzgerald and your corker of a book, A Guide to Life in the National Capital, surfaces under this writer’s nose in the op shop. (The copy we found has the moniker V.V. McCabe scribbled on the front cover. If that’s you and you’d like it back, just give us a call.)

Sadly no longer with us, Fitzgerald was a satirist and a staunch defender of the national capital, if those two can work together in the same sentence. Published in 1969, it was billed as the only booklet to tell Canberra’s real “unauthorised” story.

Apparently in his day, unless you were a “diplomat, lobbyist or lawyer” there was no way you could afford to live in Mugga Way, known as the “sublime street of status”. Anyone who was anyone lived in “old Canberra”: Forrest, Deakin, Red Hill and “in a small part of Yarralumla”.

Nice yet ambitious folk could live without guilt at Campbell, Hughes (only Hughes Heights though), (upper) Aranda, Garran, Pearce and Torrens. The author’s own suburb, Farrer, was coldly referred to as North Cooma. Savagely, the northern suburbs of O’Connor, Lyneham, Dickson, Downer, Watson and Hackett were “best left to the clerks and panel beaters”.

Once you landed your job, so you knew which suburb you could live in, Fitzgerald offers helpful advice on what to do with all those pesky hours that made up a day in 1960s Canberra. His initial advice: “Finding something to do in Canberra is easier than finding somewhere to go after you’ve done it”. This is especially so, he writes, during daylight hours.

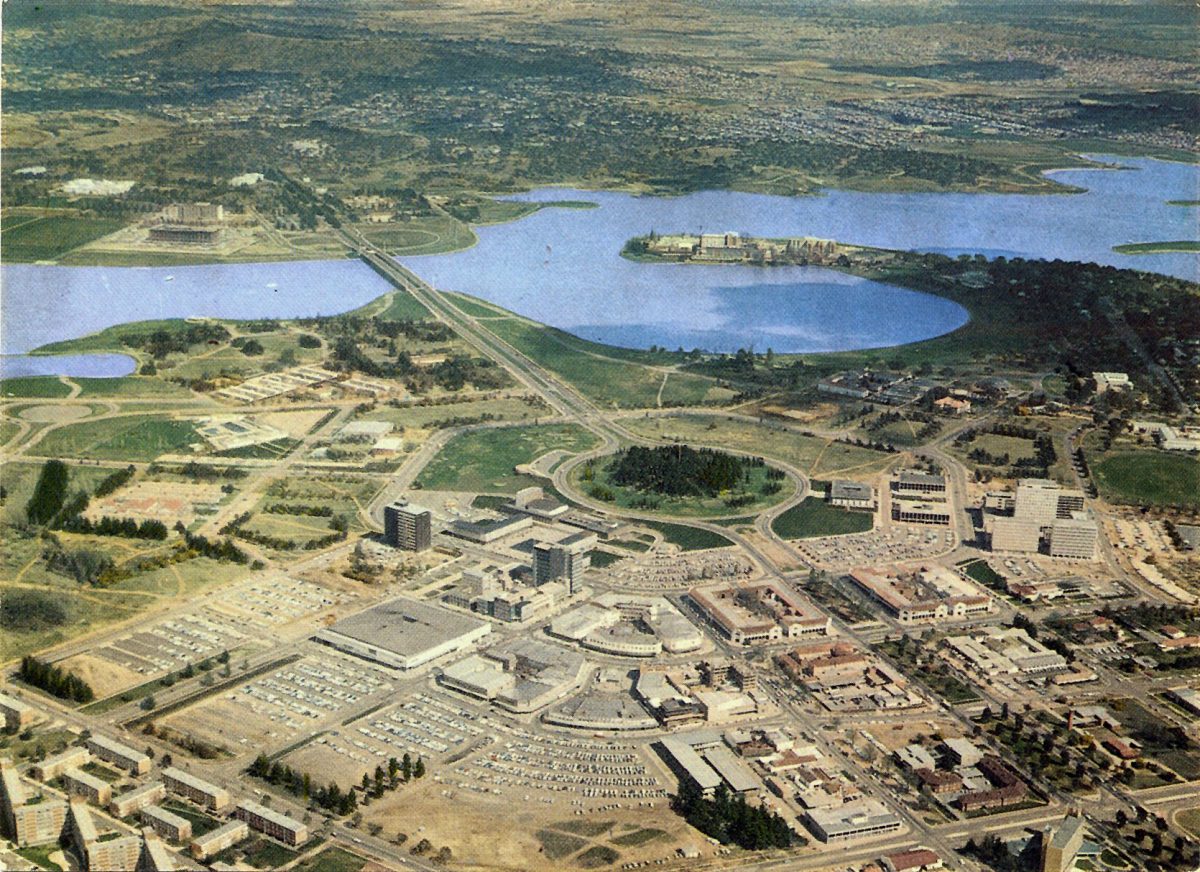

An aerial shot of the nation’s capital taken about 60 years ago, the era of Fitzgerald. Looks like there’s a fair bit missing. Photo: Region Media.

Establishing a garden, he says, could also help kill a few days. With new Canberrans entitled to 40 shrubs and 10 trees when they moved in, picking them up, one at a time, from the Yarralumla Nursery, could also help occupy one’s time.

Chances are though, with Canberra weather probably as confused then as it is now, you would probably spend most of your days going back and forwards to the nursery to replace trees that the wind/sleet/snow/heat/kangaroos/foreign objects/neighbours destroyed. (And if you always wondered why winter in Canberra seemed so long, it was, says Fitzgerald, because that season lasted from three months to 10 months.)

Seems he also had a few words to say about the 1960s Canberra woman, including “she is heard before she is seen”. She was called Jill, Robin, Felicity or Prudence and was probably married to Roger, Roland, Michael or Derek. And their children? Jeremy, Matthew, Rupert, Hugo or Anna, Isobel, Fiona or Kate.

“Apparently she drives fast, under the impression that oncoming traffic will part like the Red Sea for her and is just as formidable on the footpath. Sometimes, in her effort to be ‘naice’ [different or unusual], her voice sounds like she is in pain.”

And in a sort of a compliment, he describes her as “one of the beautiful people, although straight of leg, flat of bust and long of nose” – and seldom seen without a bow in her hair.

OK, here’s what you’ve been waiting for. Sex. The smutty bits. Canberra’s underbelly/underpants/underwhatever when it comes to a popular pastime in the nation’s capital. Please read on while our blush subsides.

In the booklet, Fitzgerald reckons adultery in a 1960s Canberra was second only in popularity to gardening – and lays it out for all to see. Seems Canberra had two kinds of it. The illicit and the licit. The former, apparently, flourished at places of tertiary and secondary education, in pine forests and in cars parked by the lake. All he says about the licit kind was that the maternity section of The Canberra Hospital was kept very busy during the summer months because of what happened in the winter months.

To complete this view of a long-ago Canberra, Fitzgerald also took a pencil to his own kind, saying the nation’s capital had more journalists, 300, than police.

But more than 60 years on, some things still ring true.

“Journalists like policemen are a necessary evil,” he writes. “A policeman will try to stop you doing something because the law says it is wrong. A journalist doesn’t mind what you do as long as afterwards, he can tell the world what you’ve done. Either way, you are unlikely to try it a second time if one of them has observed what you are up to.”