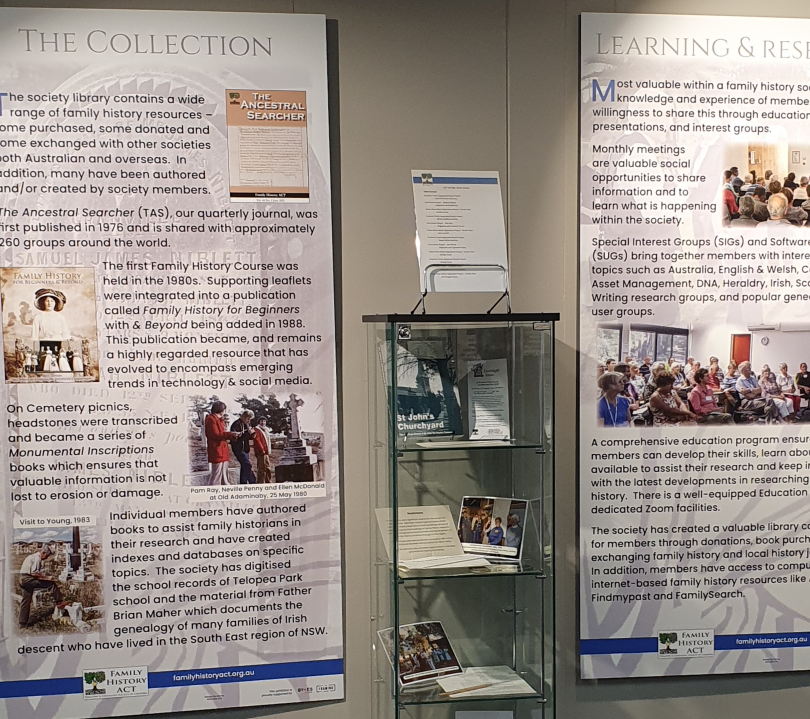

A section of the family history exhibition at the ACT Heritage Library. Photos: Family History ACT.

Family history may be the most personal branch of the discipline, but it is not for the fainthearted, especially with the added investigative power of DNA analysis.

Not only are there skeletons in many family closets, but our ancestors were often not pleasant characters but captives of their times, when race mattered, slavery was legitimate business and women had few rights.

Family History ACT president Rosemary McKenzie has been an avid researcher since she was a teenager when her terrified mother feared she would open the door on her family skeletons.

That turned out to be the fact that her mother was born two years before her parents were married, uncontroversial now, but for a devout churchgoer, a horrific secret.

Some unearth illegitimate offspring and infidelities; murderers, thieves and crooks; or some who made their money from the-then legal but immoral slave trade.

“If you’re not prepared for surprises, not prepared to find something that you maybe don’t want to find, then it’s not for you,” warns Rosemary.

“It doesn’t matter how you work it, our ancestors were not all the current flavour of the month.”

Family History ACT president Rosemary McKenzie.

She says there is always the risk that you will find out something you had rather not known, such as a Queensland friend who discovered that her grandfather wasn’t her blood ancestor.

People disappeared into asylums with mental illness or lied on their marriage certificates if they had convict ancestry.

“You have to consider what society was like a couple of hundred years ago,” says Rosemary.

Not that it seems to have deterred that many as family history rides a boom fed by a secular identity crisis and hunger to know where you come from, the advances in digital research tools and DNA testing and, of course, the popular television shows featuring celebrities.

For many starting to investigate their family history, the first introduction comes with the big ancestry websites, but the ACT has its own research treasure in the National Library of Australia’s Trove digital resource, including its collection of digitised Australian newspapers.

“Anybody who is a member of a family history society who has not used Trove has obviously only been in for a minute,” says Rosemary.

August is Family History Month and the NLA has an illuminating blog from family history librarian Jack Ennis Butler, The past is present: Putting family history in context.

While plenty of sleuthing happens in the digital space, Rosemary wants to remind family researchers that there is still plenty of useful material that is not online, as well as advice from heritage and historical societies such as hers, now nearing its 60th year.

As part of Family History Month, an exhibition at the ACT Heritage Library is celebrating the work of Family History ACT, which began as the Heraldry & Genealogy Society of Canberra in 1964, its own history and where the future lies.

The exhibition features many photographs, artefacts and ephemera, and discusses the importance of family history and why and how it should be done. It is likely to be extended due to the lockdown, and some of the associated talks are rescheduled.

For Rosemary, family history is a pursuit that connects her personally to the past and provides a broader picture of how people, including women and children, actually lived.

That’s a far cry from the white, male, military view that has dominated the study of history.

“You actually cultivate a relationship with that point in time,” says Rosemary.

A display cabinet of memorabilia at the exhibition.

She has ancestors who lived and worked in London as silk weavers until the industry declined about the middle of the 19th century.

“That’s what drove my ancestors to emigrate to Queensland,” Rosemary says. “When your ancestor is tied to it, it makes it so much more interesting.”

Rosemary says people may start online, but many realise that the extra information and networking that societies such as Family History ACT provide can take them further when they hit an investigative wall.

The Family History ACT library at Cook, for example, has more than 20,000 publications, including microfiche and microfilm, 99 per cent of which are not online.

These include births, deaths and marriages, headstone inscriptions from cemeteries, and books.

Now that the online revolution has occurred, Rosemary sees a changing role for her organisation, moving to a more specialised role.

“It seems now that everybody is doing it. We’ve become more specialist in assisting individuals and small groups and reaching out to regional areas,” she says

That means working with like-minded organisations within the Canberra region and providing a personal touch.

“They all have different flavours, but all are interested in Canberra region family history and how it affects the family and social community in the region,” Rosemary says.

“We provide complementary personal relationships rather than just sitting at home in our pyjamas at three in the morning assessing indexes or sending emails.”

Family History ACT has 600 members and offers a range of services and special interest and software user groups that meet regularly.

It publishes its own journal and exchanges journals with over 200 overseas societies and helps people publish their own family histories, made much easier by digital printing.

While the organisation began with a strong Anglo-Celtic influence, the many waves of immigration have diversified its membership and connections.

The NLA says the Trove newspapers can also shed light on Australia’s migrant populations and their immigration experience.

For Indigenous people wanting to piece together their often disrupted lineage and connections to country, the organisation refers them to the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, which has a very strong family history group and the required expertise.

To learn more, visit the Family History ACT website.