James Mollison shows an un-crated Blue Poles to art critic Robert Hughes. Photo: NGA.

“Those days sitting in the Fyshwick warehouse with Monets coming in the back doors and Fred Williams on the boards were pretty exciting ones,” says former National Gallery of Australia staff member Hester Gascoigne as she recalls the beginnings of the institution.

James Mollison, its founding director who has died at the age of 88, led the National Gallery through those remarkable formative days. The announcement of his death last month has prompted memories from people who were there as the national collection was engineered from the ground up.

Mollison was the driving force with his bold acquisition policy ahead of the official opening in 1982.

Originally an executive officer for the Commonwealth Art Advisory Board and exhibitions officer in the Commonwealth Prime Minister’s Department, he was initially made acting director in 1971 before permanently assuming the position in 1977.

“He was energetic, a visionary, all the things that people say about him,” says Hester, who worked at the Gallery for years and is the daughter of Canberra’s most celebrated post-war artist, Rosalie Gascoigne.

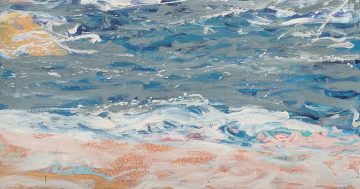

Rosalie Gascoigne’s Suddenly the Lake, reflecting Lake George. Image: File.

Rosalie and her husband Ben Gascoigne came to Canberra during the post-war population boom, when the city was developing a new identity as a place of intense energy and creativity. Ben was posted to Mt Stromlo as an astronomer and Rosalie was, as Hester says, driven to find more in life than being a housewife and mother.

Her powerfully evocative installation artworks drew their inspiration and materials from the Canberra landscape. She loved nothing more than rummaging through a good country tip for discarded, weathered objects that spoke of the baking sun, icy winters and bone dry seasons.

In Mollison, she found someone who “spoke the same language” and became a friend of the Gascoigne family – as a student Hester even spent some time as his cleaning lady.

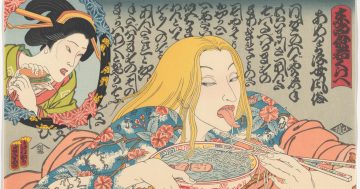

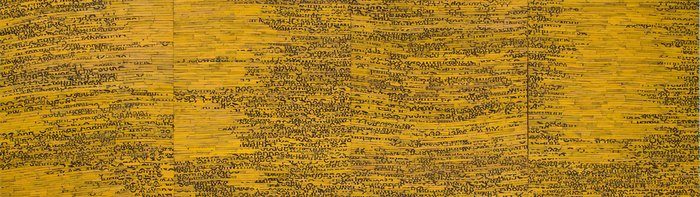

Rosalie Gascoigne’s Monaro, 1989, made with synthetic polymer paint and soft-drink crates. Photo: File.

“James took risks and had the benefit of a government that was completely behind him,” she says of the collecting strategy that included major acquisitions like Jackson Pollock’s Blue Poles, and major donations from Arthur Boyd and Sidney Nolan.

“He had a supportive board and supportive chairmen for the most part, and he had the capacity to draw like-minded people around him. That made a big difference”.

Part of his mission included making regular circuits of local galleries, often with a curator in tow. Immediate, close contact with the Canberra arts world fed local engagement with the NGA at a time when Canberra was a much smaller town.

It was also a time when the Gallery staff numbered less than 30, a far cry from the large national institution it is now. That meant Mollison’s role as director was far more hands-on.

Hester Gascoigne remembers him conducting archival interviews with Rosalie himself and dashing in and out of the Fyshwick warehouse while building donor relationships with some of the wealthiest benefactors in the country.

After almost 20 years he left the NGA in 1989 to take on the role of director of the National Gallery of Victoria.

NGA Director Nick Mitzevich said last week that Mollison was one of Australia’s greatest museum directors.

“His fearless risk-taking inspired an entire country to talk about art,” Mitzevich said. “His impact was much wider than just art circles, wider than just galleries. He had an impact on the debate about art and culture in Australia.

“The artistic legacy of the national collection owes him a great debt. He was collecting history as it was being made.

“Many remember him for Blue Poles but his legacy is so much greater – that work was emblematic of his foresight and the courage that he displayed over two decades of developing a truly great national collection for the people of Australia.”