A committee inquiry recommended extra resources be allocated to allow more students to visit Canberra on excursion. Photo: MOAD.

The ACT Government will “analyse and consider” how civics is taught in the city’s public schools after a damning national report.

The National Assessment Program – Civics and Citizenship 2024 (NAP-CC) quizzed Year 6 and Year 10 students from across Australia on their knowledge of our democracy, civic institutions, system of government, and the rights and obligations of Australian citizens.

The results, assessed by Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA), show both years underperformed in meeting the proficiency standards in civics compared to when the test was last taken in 2019.

Year 10’s “proficiency” fell to 28 per cent nationally (from 38 per cent in 2019), while Year 6 measured 43 per cent (53 per cent in 2019).

ACARA concluded these marked the worst results on record since testing began in 2004.

Across the jurisdictions, the ACT recorded the highest proportion of students achieving the standard (58 per cent in Year 6 and 37 per cent in Year 10); the Northern Territory recorded the lowest (27 and 18 per cent, respectively).

ACARA CEO Stephen Gniel remained upbeat, pointing out most students maintained a “a high degree of trust in civic institutions”, and “rate citizenship behaviours, such as learning about Australia’s history, as important”.

But he said the results highlighted “how we need to continue to support our teachers and educators with high-quality training and resources to help them effectively deliver engaging civics and citizenship education”.

The report notes participation in civics education at Australian schools has decreased over the years, particularly at the Year 10 level, with the largest decline observed in excursions to parliaments or law courts.

“This declining trend in student performance has also been observed in other recent international civics and citizenship assessments,” ACARA says.

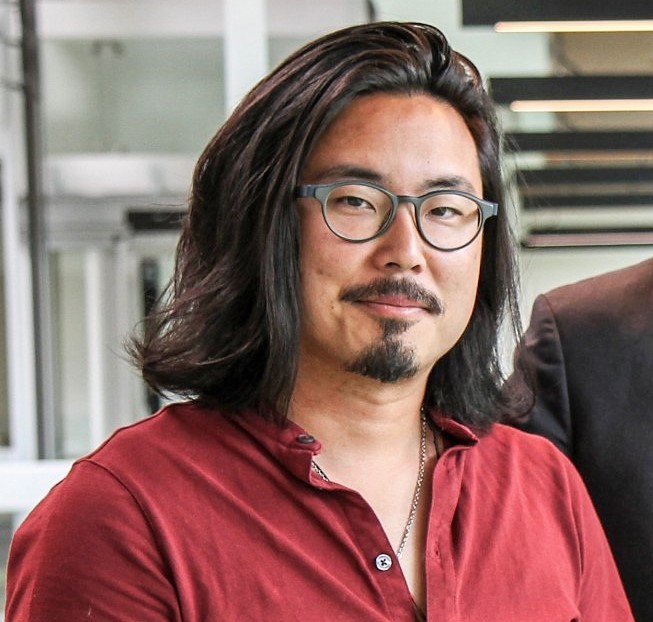

Associate Professor Mark Chou from the Australian National University’s Crawford School of Public Policy agreed civics education in Australia had faced “a range of implementation issues”.

“If a democracy is a political system governed by the people, the people should have a certain level of political competency or knowledge in order to govern effectively or, to quote Don Chip, to ‘keep the bastards honest’,” he told Region.

“But … civics and citizenship education has really never fulfilled its mandate in Australian schools.”

Professor Chou said it had been increasingly crowded out in the national curriculum by other studies of society, history and geography, at the same time as a lack of professional development for teachers had left them feeling “under-prepared” to teach it.

Associate Professor Mark Chou, ANU Crawford School of Public Policy. Photo: ANU.

“A 2008 study revealed 91 per cent of Australian teachers surveyed felt civics and citizenship education is fundamentally important to our nation, yet they did not feel competent or confident to teach the content,” he said.

“This raises equally important questions about what education degrees at universities include.”

He said the curriculum also placed too much emphasis on “formal politics” such as parliament, voting and political parties “which isn’t always directly relevant to most students’ lives”.

“Civics and citizenship education should utilise action-based learning to encourage a sense of agency in students … This is effectively about putting civics and citizenship education into practice so it’s not just an abstract subject about settler-colonial history or what takes place in Canberra or during election time.”

Civics is currently included in the national curriculum but the states and territories, and individual schools, have a large degree of autonomy in what importance they give to it.

Professor Chou argued civics should be instated as a “compulsory standalone subject in secondary schools”.

“We need to stop thinking of civics and citizenship as a second-order subject in high schools.”

The national curriculum is not due for an overhaul until 2027, but a recent Federal Government inquiry into “civics education, engagement, and participation in Australia” has handed down 23 recommendations.

Alongside allocating extra resources to “allow more students to visit Canberra” and “strengthening access to civics education for adults”, these recommendations include “nationally aligned and mandated civics and citizenship content in the Australian Curriculum and better support for teachers through high-quality professional development”.

“The committee heard clear evidence the quality of formal civics education varies considerably between the states and territories … which means many young people are not getting the information they need to be informed and responsible citizens,” committee chair Carol Brown said.

A spokesperson for the ACT Education Directorate said it was encouraging to see ACT students – across public and private sectors – were the highest performers nationally on the test even if “there has been a decline … consistent to those observed … nationally”.

ACT public school students study civics and citizenship in years 3 to 8, while it’s up to the school to decide to offer it in years 9 and 10.

“ACT public schools will continue to teach civics and citizenship in line with the Australian Curriculum,” the spokesperson said.

“The ACT Government will continue to analyse and consider the results of the NAP-CC report.”