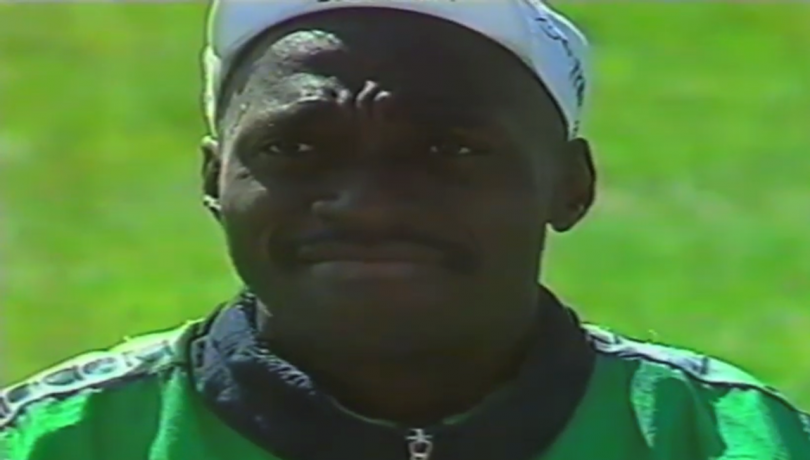

Horace Dove-Edwin shocked the athletics world when he claimed the silver medal in the 100 metres final at the 1994 Commonwealth Games. Photo: File.

It was incredible watching the feats of rising US teenage sprinter Erriyon Knighton on the track at the recent Tokyo Olympics. The 17-year-old has been dubbed the next Usain Bolt after eclipsing the Jamaican’s junior records and then making the final of the 200 metres at the Tokyo Games, where he finished fourth.

Blessed with blinding speed beyond his years, the naturally gifted Knighton is a superstar in waiting, and it’s no surprise he is on the radar of American football scouts. Having excelled as a wide receiver and sometimes running back and kick returner in high school football, the speed machine turned to athletics where his gift is most suited.

But the NFL is watching him and will be sniffing around and applying pressure for him to return to the big-money sport as his star rises.

Seeing Knighton attracting interest from American football brings flashbacks of the Canberra Raiders’ audacious attempt to lure Sierra Leone sprinter Horace Dove-Edwin to the national capital following his shock silver medal in the 100 metres final at the 1994 Commonwealth Games in Victoria, Canada.

For a brief window of time, Dove-Edwin’s story captured the imagination of the world.

Having fled the war-torn West African nation of Sierra Leone, the penniless athlete with no coach, no entourage and no achievements of note, finished second to legendary British athlete Linford Christie, beating accomplished speed merchants Frankie Fredericks from Namibia, Michael Green from Jamaica, and Olapade Adeniken from Nigeria to claim the silver.

It was the first athletics medal Sierra Leone had ever won in international competition, and while Christie celebrated his win that everyone expected, the Canadian crowd was glued to an elated, highly emotional Dove-Edwin who bounced around the stadium draped in his nation’s flag.

At the time, Tim Sheens was head coach of the Raiders, having led the club to premierships in 1989 and 1990. He was also just a month away from leading the Green Machine to the 1994 title, but as an innovative pioneer of Australian rugby league, the master coach was always future-focused, seeking new talent from far and wide.

Ruben Wiki, John Lomax, Quentin Pongia and Sean Hoppe were all inspired recruitments to the club from New Zealand around that time, and the luring of flying Fijian Noa Nadruku was a masterstroke. While a West African sprinter who knew zilch about rugby league was a massive stretch, the Raiders hierarchy was interested.

Casting one eye to the 1995 ARL campaign, Sheens saw the raw potential in Dove-Edwin and put out feelers to lure him to Canberra while the world watched on.

But no sooner had the Raiders tabled an offer to the overnight track sensation for a trial at the club when the rags-to-riches story collapsed.

Dove-Edwin was a drug cheat.

Turns out he was juiced up on steroids, with his post-race urine sample returning a positive result for stanozolol.

Stripped of his medal, Dove-Edwin never heard from the Raiders again.

In all likelihood, the experiment would have failed. The chances of the African carving up on the wing for the Raiders in the then-ARL competition would have been close to zero. But it was a sign of the power of the club – and Australian rugby league in general – at the time that in those few days of media hysteria, the Raiders were making waves.

In the 1980s and 1990s, there were a few unspectacular examples of athletes from other disciplines attempting to make it in rugby league. Shane Whereat was a former sprinter who played 73 first-grade games for the Sydney Roosters and Parramatta Eels with some moderate success, and Olympic 400-metres track star Darren Clark joined the Balmain Tigers while on sabbatical from athletics in 1991 but failed to progress beyond reserve grade.

World champion boxer Jeff Fenech also played a single reserve-grade game for the Eels, while American Greg Smith was recruited to the Newcastle Knights in 1999 and played one horror game on the wing in first grade and was never sighted again.

Even the fastest man on the planet, Bolt, looked a little silly trotting out as a footballer for the Central Coast Mariners in a few A-League trial games in 2018.

For Dove-Edwin, his exposure as a fraud had him fearing for his life if he was to return to Sierra Leone after the Commonwealth Games. Only a month earlier, Colombian footballer Andres Escobar was murdered just five days after his own-goal saw the South American nation sent packing from the 1994 FIFA World Cup.

Dove-Edwin was spooked by his sudden rise and spectacular fall. He even admitted to becoming suicidal. He eventually fled to California and began a new life a long way from war-torn West Africa, and even further from freezing Sunday afternoons at Canberra Stadium.