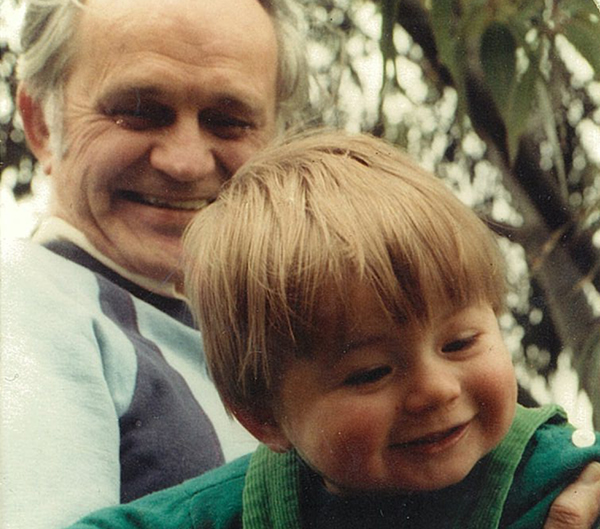

On my desk there is a photograph of my Grandfather and me at the age of one. He is holding me in his arms and smiling down at me with that unique union of love and joy that only the innocence of young life can inspire. My Grandfather, John Bailey, had three daughters yet in the hope of one day having a son he kept in his heart the name Steven. And, as a result of my biological father not really being present in my life, I suppose he did have a son, in the form his first grandson named Steven John Bailey. It was inevitable that Grandpa and I would share a life lasting affinity for one another.

Grandpa shared with me his love for piano music and he taught me to play pool. He was a self- taught linguist who spoke over ten languages (and many of their dialects). As a child I would often open a rather large dictionary and test his vocabulary. He would know the meanings of words he had never heard before only because he could identify the Latinate or Greek syllable. During his long afternoons of sitting in the sun he would explain things like why it was important to maintain a low inflation rate, and how the Left’s approach to industrial relations was a communist conspiracy – with a twinkle in his eye. We didn’t agree on everything, but agreeing wasn’t the point. The point was to share one’s life while one had it.

One night, a few years ago, Grandma called me and said that she I thought I’d better come to Adelaide. I booked the next flight and was in the hospital the next morning. His frail and pained body managed to muster some semblance of that joy he held when I was a child in his arms. Grandpa had suffered a terminal illness for his entire retirement, and I was told that he had hours to a few days to live. As the hours continued more family arrived, and luckily I was allowed to stay by his side on his last night of life. Very few words were spoken that night but as our eyes met between his sleep and our pain – words didn’t really matter – which was rare.

There came a time when the nurses informed me that they were going to administer a high dose of morphine. I objected as my mother had not yet arrived from interstate and I knew that he would have endured any pain to see her once more. I instructed the nurse to give him a third of the dose that was in the syringe. The nurse obliged, and Grandpa was able to see and speak with my mother one last time.

When the pain and discomfort became too much he was administered the remaining morphine. We closed in around the bed.

I felt his hands that once played Chopin waltzes slowly releasing their grip on mine whilst, equally, my grip increased in vain defiance. And as he drifted away I imagined the languages leaving his beautiful mind to lifeless yet exhausted matter. I imagined, and hoped, that he could hear us telling him that we loved him, and that we always would.

I never want to be euthanised, regardless of the pain, and I’ve told my family this. That is my choice, and one day I may have to live with it. I once opposed voluntary euthanasia but now I support it. I support a person’s liberty to choose. For the people who say that it’s important not to confuse emotion with reason, I say this: emotion and reason are not mutually exclusive. Emotion and reason need one another; indeed emotion and reason cause one another.

It’s time for the Andrew’s Bill to be repealed, and for the ACT to make her own judgements on voluntary assisted dying.