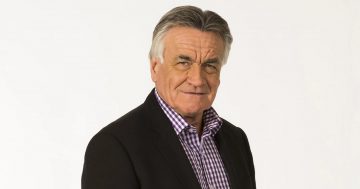

The sacking of Phillip Ruddock caused me to contemplate a number of issues.

Firstly, I have served with Phillip Ruddock on a couple of ministerial councils and found him to be a warm and honest man. A little dry perhaps, sometimes appearing to lack humour and very semantic, he was nonetheless a man of conviction and principle. He did not deserve this execution.

Secondly, as a former whip of some nearly seven years I have some experience in what whips are supposed to do in the House. I do think that the role of the whip is misunderstood by members of parliament and not known at all by the general public. This is clear from the actions of the PM.

The term has its origin in the British political history many hundreds of years ago. It comes from the hunting practice of whipping the errant hounds back into the pack during a fox hunt.

The roles differ from country to country but in the Westminster system there are common elements.

The whip’s job falls mainly into three categories: parliamentary business, parliamentary precinct business and pastoral care.

Parliamentary business is the business in the chamber. The legislative business is governed by the leader of the house and the government whip is instrumental in working with the leader of the house in controlling private members’ business. Whips also manage members’ attendance in the chamber (and by extension their absences) by granting leave or arranging pairs with opponent whips.

The opposition (and sometimes a crossbench) whip does the corresponding job for those sides of the House.

This entails developing a comprehensive knowledge of standing and temporary orders, including length and precedence of debates, management of speaking times and lists, and requires negotiating skills to talk to other whips on the business of the day. Mostly, this goes ahead without hitch, provided whips have a mutual respect for each other.

Parliamentary precinct business differs depending on the size of the parliament. In large parliaments, the whips assist the speaker only minimally, but in smaller parliaments the relationship is more extensive. Responsibility can include assisting the speaker in the development of the parliament’s budget, advice on security, distribution of resources such as car parking, allocation of offices, members’ entitlements, and proposals to alter the standing orders or operational orders and sometimes media access.

Pastoral care is the often ignored role of the whip. This responsibility is not discharged that well in most parliaments because the whips are unaware of the role and some are reluctant to get involved with the personal issues of their members. It is in this area that Whips come to know a lot about the personal peccadillos of members. They are the people who seek to shelter the government, opposition or crossbench from any smell of scandal. The paucity of such scandals can sometimes be credited to effective whips.

The whips are supposed to provide counselling and training for new members and be on the lookout for members’ welfare. This is a tough profession and is a dangerous place to work. They should be aware of the symptoms of a black dog prowling the hallways and intervene to save members from themselves. The lack of this aspect of the job has cost a couple of pollies their lives.

In some parliaments, whips act as party room or caucus secretaries and are the public face of those forums. In this role they are often seen as the messenger of decisions delivered for public consumption to ensure the privacy of the party room or caucus.

In addition to these specific duties, the whip is supposed to create a rapport with the opposition (particularly backbenchers) and crossbenchers so that even in times of all out warfare, there is at least one door open to convey sentiments of compromise to achieve a positive result.

Whips are supposed to be parliamentarians first and politicians second. They are their party’s emissary to the parliament and provide a service to the parliament before the party they belong to. This is where many whips come unstuck.

It is not the job of a whip to protect the back of the first minister; the whip is not the first minister’s guard dog.

However, it is the whip’s job to interact between the backbench and the cabinet and particularly to the first minister. In this role however, the access to the first minister must be easy and respect must be reciprocal. The delivery of unpleasant and inconvenient truths is hard enough without the spectre of a beheading.

The whip job is a particularly difficult one in which the occupant of that office must possess not only the respect of but the confidence of one’s own colleagues, those on other sides of the chamber but also be an effective communicator and receptacle of the knowledge of parliamentary procedure.

It can be nigh on impossible to be a political operator and an effective whip.

So… did Phillip Ruddock deserve the chop? Was he removed because he did not discharge the duties of whip to the satisfaction of the PM? I don’t know the answer to those questions but I do know that it is rare for Cabinet members to know the slightest about what to expect from a whip.

I also know that when whipping boys are needed, the shooting of the messenger is the order of the day. The only sin I can detect is that Ruddock did not have conversations with the PM over backbench dissent and give him an honest and frank appraisal of difficulties coming over the horizon.

I’ll bet though that he wasn’t encouraged to meet with the PM on a regular basis for the PM to receive this information, and I’ll bet that if he had asked to see the PM, he would have been blocked by the guard dogs in the PM’s office.

Phillip Ruddock is a professional parliamentarian and was an ok politician; there is a difference. But as chief whip (because a large parliament has a number of them), he has carried the can for a disastrous episode in the government’s fortunes.

For more information on the roles of whips in small parliaments, I refer readers to my article in The Parliamentarian, Issue 3, 2012.