Nearly 500 public homes are currently under construction or in design in the ACT. This one was opened by Housing Minister Yvette Berry on 20 August. Photo: Yvette Berry Facebook.

Housing affordability is a crisis in Australia. For government, it is a wicked problem. It can’t be solved with virtue signalling or emotes to ‘do something’. We need to have some difficult conversations, but politics hates that. We want answers now.

With an election in October, politicians – actual and aspiring – have landed on public housing as the magic bullet.

The truth is, public housing won’t dent the housing crisis. We can’t afford it. Public housing is too expensive and more of it will only encourage demand for public housing by turning government into the landlord of choice. What’s worse is that candidates promoting this ‘solution’ know it won’t work.

It’s time you heard the reality about public housing.

What’s the problem we’re trying to solve?

It’s easy to spell out the problem about homelessness and the housing crisis affecting low-income Australians. It’s easy to identify the problem: houses cost too much, there aren’t enough, too many people can’t afford them.

But read the opinion pieces published across Region platforms again (Social Capital? This election, let’s fix market failure and Government can’t afford to turn its back on community sector in its time of need).

Notice something? They define the housing crisis in granular detail but stop short of explaining how much their solutions will cost.

Take Independent for Canberra’s Thomas Emerson in his oped When did we give up on fairness?

Emerson wrote: “Most of the Canberrans I’ve met on the campaign trail have a strong social conscience. They believe we should feed the hungry and house the homeless. They want to live in a fair society, but our public housing stock has decreased by almost nine per cent since 2011. During the same period, our population has grown by 30 per cent.”

He says we should first elect more Independents for Canberra candidates (of course!)

He wants more public housing, right? But he doesn’t tell you how much it would cost, although he casually references how much housing stock he thinks we need.

Housing ACT has about 12,000 dwellings on its books. So, if Emerson wants public housing to meet population growth, we would need 30 per cent more public housing.

Those extra 3600 homes (30 per cent of 12,000) would cost around $2 billion. At a minimum.

The ACT is wealthy, we can afford public housing, right? Nope

Not in 2024 with the current building regulations, the standard of public housing built in the ACT and the dire state of ACT finances.

Understand this: modern public housing is very modern. They aren’t the shoeboxes that were knocked down on Northbourne Avenue a few years ago.

Scroll through Minister for Housing and Suburban Development Yvette Berry’s Facebook feed and you’ll find multiple examples of new public housing, including this development she opened last week (20 August).

This is the quality of public housing being built in 2024 in the ACT. Would you live here for 25 per cent of your income?

Sustainability, housing choice, adaptability, energy efficiency, low-running cost and amenity are all important for housing – but at what cost?

So how much does it cost?

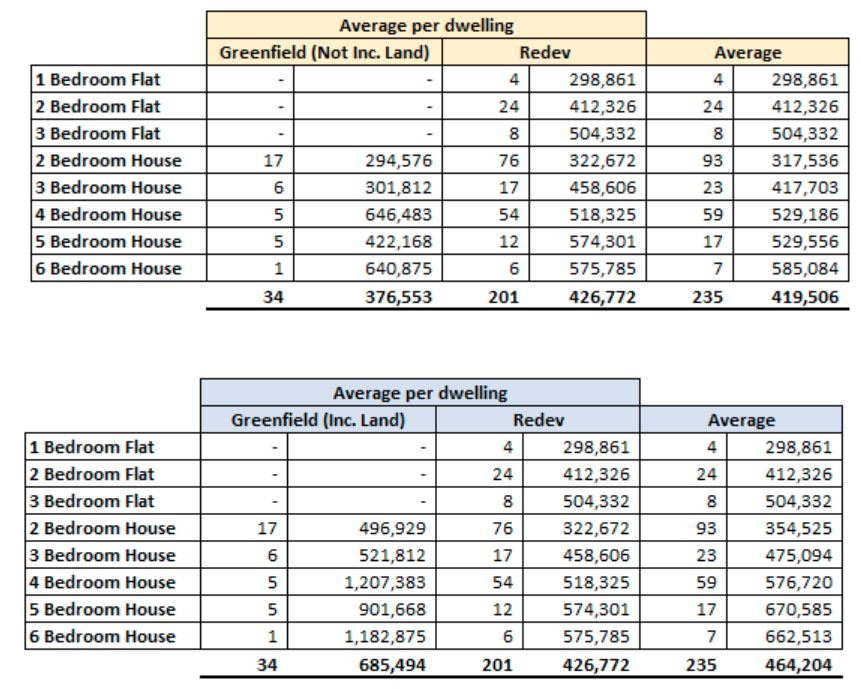

On average, public housing in the ACT costs anywhere between $500,000 to more than a million dollars per dwelling, based on ACT Government figures. Each home also costs the government about $10,000 a year to maintain. Even on the back of an envelope, the numbers get very scary, very fast when you realise what politicians are promising.

Of course, building costs have only risen since these estimates were calculated in the period 2019-20 to September 2022 and released in January 2023, so these are more than optimistic estimates.

Public housing cost per dwelling (Question on Notice tabled January 2023). Table: Housing ACT.

Unlike most, the ACT Greens are very open about the cost.

They want to build 10,000 public homes in 10 years and estimate the capital cost at $5 billion to $9.5 billion. Their maths is correct (based on $500,000 to $1 million per dwelling).

But that assumes land will be sold from the Suburban Land Agency from ACT Government releases to Housing ACT at a 50 per cent discount, so it could cost well over $9.5 billion.

Won’t building the homes solve the problem?

Not a chance.

We’re trying to help people in crisis. People in desperate need of a home.

The properties we’re building now will only fuel demand because the government will be the landlord of choice. Check out those photos again. Who wouldn’t want to get a home like that for 25 per cent of their income?

Income eligibility to access public housing is quite low (up to $71,000 a year for a family with two dependents).

This is where it gets brutal. As harsh as it sounds, taxpayers can’t afford to build million-dollar homes and charge about $340 a week rent (25 per cent of $71,000).

And then the $10,000 a year for maintenance and rates (Housing ACT pays rates to the ACT Government in a money-go-round).

And then there’s lifetime tenure.

Golden handcuffs?

In the ACT, public housing is not ‘temporary’.

Once you’re in public housing, you have tenancy for life. Why would you leave a million-dollar home when you’re paying 25 per cent of your income to enter the private rental market? That will only put more pressure on the waiting list.

And once a home is occupied, it’s off the market forever.

That’s the problem the ACT Government faced when they tried to relocate tenants to sell their property and reinvest the proceeds through the Growing and Renewing Public Housing Program.

There are more problems when it comes to construction in the ACT.

Where are the workers coming from?

If you’re looking to build or renovate, you better hope the government doesn’t try building an extra 1000 or more public houses a year because we don’t have the workforce.

In a good year, across the entire ACT, about 5000 new dwellings are built.

The Greens’ public housing target would increase that by 1000 a year (20 per cent more), and that’s before the Albanese Government’s Homes for Australia plan that promises “1.2 million new, well‑located homes by the end of the decade from today [1 July 2024]”.

According to the Master Builders Association, the industry’s biggest challenge is not having enough workers. The MBA estimates the ACT will need 7000 more construction workers by November 2026 to meet current targets.

So that raises two questions: where will the workers come from and, ironically, where would they live?

The ACT also doesn’t have the money. It would all be debt – in addition to other promises on our tab such as light rail, the theatre redevelopment, a new convention centre … You see the problem?

The housing crisis is a wicked problem. If it weren’t, it would have been solved already.

If you are a candidate and are promising to fix the issue with public housing, you need to answer some pretty horrid questions that governments have avoided for decades:

How many public houses are you planning to build? Where will they be built? At what density? How long will it take? Where will the workers come from? How will you decide who gets them? Will there be lifetime tenancy? How will you limit demand? At what standard will they be built? What taxes will you raise, or what services are you going to cut or how much are you prepared to borrow?

Public housing in Dickson. The new homes include a range of two-bedroom townhouses to four-bedroom units and meet a minimum six-star energy efficiency rating. Photo: Housing ACT.

The reality is that solving the housing crisis isn’t about choices – it’s about compromises.

Until candidates come clean, especially in light of everything else they promise to fix, they’re making promises they know they can’t keep, and to the men, women and children in need, that false promise is cruel.

Whatever the solution to this crisis is, it’s not public housing.