A day in the garden at the Lynham Commons. Photo: Anne-Marie Delahunt.

Canberra is a place for big ideas and vision. It’s also a place where special things can happen locally – in suburbs, in streets and even on a small patch of dirt. With the focus on development and densification in our city, it’s time to complement these big planning decisions with different ideas that start with, and involve, local communities. This is why the idea of the urban commons movement is worth considering in our city.

The idea of commons is not new – it’s actually a very old idea which focuses on identifying spaces and goods that belong to everyone. However, the modern idea of urban commons is one that has emerged as a reaction to the privatisation of many of our public goods and spaces. It’s also a response to the tendency of governments to look to the private sector and business to develop public amenity, which too often seems to have come at the cost of access and public control of these goods and spaces.

You may already be part of the urban commons movement without knowing it. If you are a member of a suburban buy nothing group that operate on social media platforms, have been part of a community garden, swapped books in a local street library, or been to a Cycle Jam or clothes swap, you have experienced some of the magic of urban commons. However, there are even more opportunities to use this idea to shape our city now and in the future.

It’s already happening – one of the most explicit urban commons operating in Canberra is Lyneham Commons. This commons was established in Lyneham in 2014 by a group of local residents and will be celebrating its birthday on Sunday 15 July. This is a celebration of how far this Commons has come since the time that a group of local residents got together to talk about a small patch of public land in Lyneham that was unloved and uncared for but had great potential to become a living food forest. Since then, these citizens have dug, planted and tilled the land. They have held community gardening days, held parties and brought life to a part of their suburb that had until then lay barren.

The founders reflect that it has been rewarding but not always easy. One of the greatest challenges has been wading through the bureaucracy to enable them to do what they need to do. Little things like ensuring the land had a water supply, finding a place to store tools, and even having the insurances in place to make this contribution, have required persistence and tenacity.

These challenges are shared experiences for urban commons all over the world, as governments and local authorities struggle to engage and partner with local communities outside traditional structures. There have been municipal governments however who value these community-led responses and worked to make it as easy as possible to make it possible.

Italy is one country where the idea of supporting urban commons is gathering momentum. Inspired by the city of Bologna who recognised the difficulties faced by a group of women who were trying to donate park benches to the city, they introduced a regulation that sought to provide a framework for the government to work with citizens to protect these common goods and spaces. This provides a framework for groups of citizens to enter into contracts with the government to participate in the care of public spaces, buildings and support cultural and educational activities that enhance the life of the city. Now cities all over Italy, including in Florence, Turin and Naples, have introduced these regulations, and in Bologna alone, hundreds of agreements with citizens have been struck. This has seen historic buildings restored, public land regenerated, community parks enhanced. Local music schools have been supported, and disused public buildings have been provided to community organisations contributing to public causes.

This approach is still in the experimental phase, and learnings are still occurring. The strength of this approach is that it provides a legal framework. Governments are responding to community interest rather than being constrained by usual procurement rules. Working through issues such as planning rules, licensing and regulatory issues have become general business, and government agencies now have a greater ability to streamline approvals. There are still challenges however – these agreements have generally been short term (only a few years) when the activities often require long term commitments. Agreements still generally have the veto of government so projects that are aligned with political agendas have more chance of success.

The concept of urban commons and embedding it into our political system is a rather radical idea which shifts residents from passive recipients of services to active players in their community. While exciting, there are also risks. A key question is how do we ensure that governments do not see this as an opportunity to abdicate their responsibilities to provide services and programs. There is also still a need to engage with what the private sector should contribute, particularly if they get commercial benefit from public goods. This is the value of this approach as a great experiment. As demonstrated by the Italian experience, this approach can draw on learnings and evolve as experience and knowledge grows. The power of technology is also starting to be harnessed, with many urban commons projects starting with a mapping of the urban commons so there is a shared understanding of what public goods exist and how government and citizens can work together to protect them.

I think the idea of urban commons has great potential as Canberra evolves and develops. What do you think?

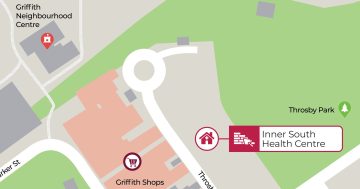

The Lyneham Commons is hosting the 3rd Birthday Party of the community food forest on Sunday 15 July, 12:00 pm – 3:00 pm at the Lyneham Commons garden, 8 Hall St, Lyneham. More information can be found here.