Carol Jerrems, Self-portrait, 1973, National Gallery of Australia, gelatin silver photograph, 17.8 x 25.4cm, National Gallery of Australia © The Estate of Carol Jerrems. Photo: National Portrait Gallery.

Carol Jerrems belongs to that brilliant generation of young photographers which burst onto the Australian art scene in the late 1960s and 1970s. A time when photography was becoming widely recognised as an art form with its own dedicated museum curators and emerging commercial art galleries devoted to photography.

Although Jerrems died at the age of 30, after only about a dozen years of professionally practising photography, she left a huge impact on Australian art.

The National Portrait Gallery’s exhibition, Carol Jerrems: Portraits, examines her career through the prism of portraiture – the artist’s central subject matter. The extensive exhibition features more than 140 of her photographs effectively displayed with an immersive intensity within a light pink environment.

A fine catalogue with intelligent, scholarly essays accompanies the show. Beautifully edited and designed, it comes with comprehensive high-quality illustrations.

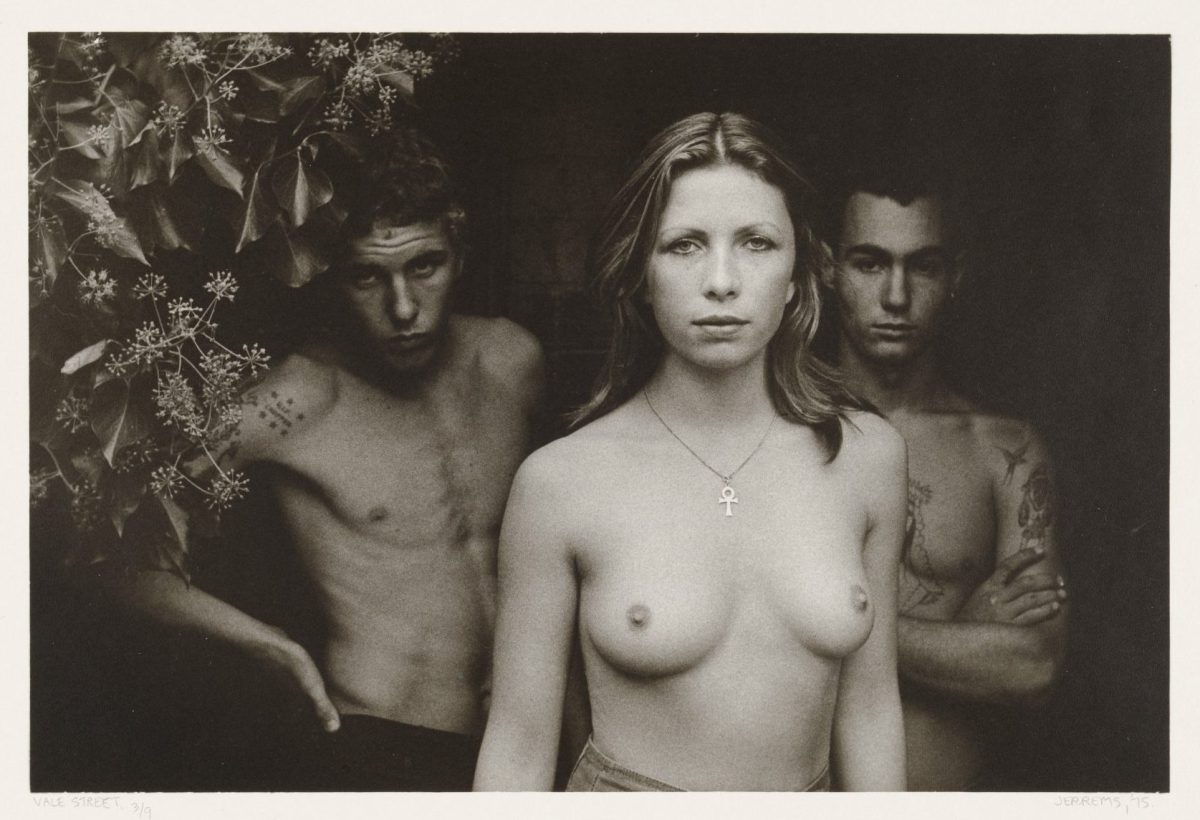

Carol Jerrems, Vale Street, 1975, gelatin silver photograph, 20.2 x 30.3cm, National Gallery of Australia © The Estate of Carol Jerrems. Photo: National Portrait Gallery.

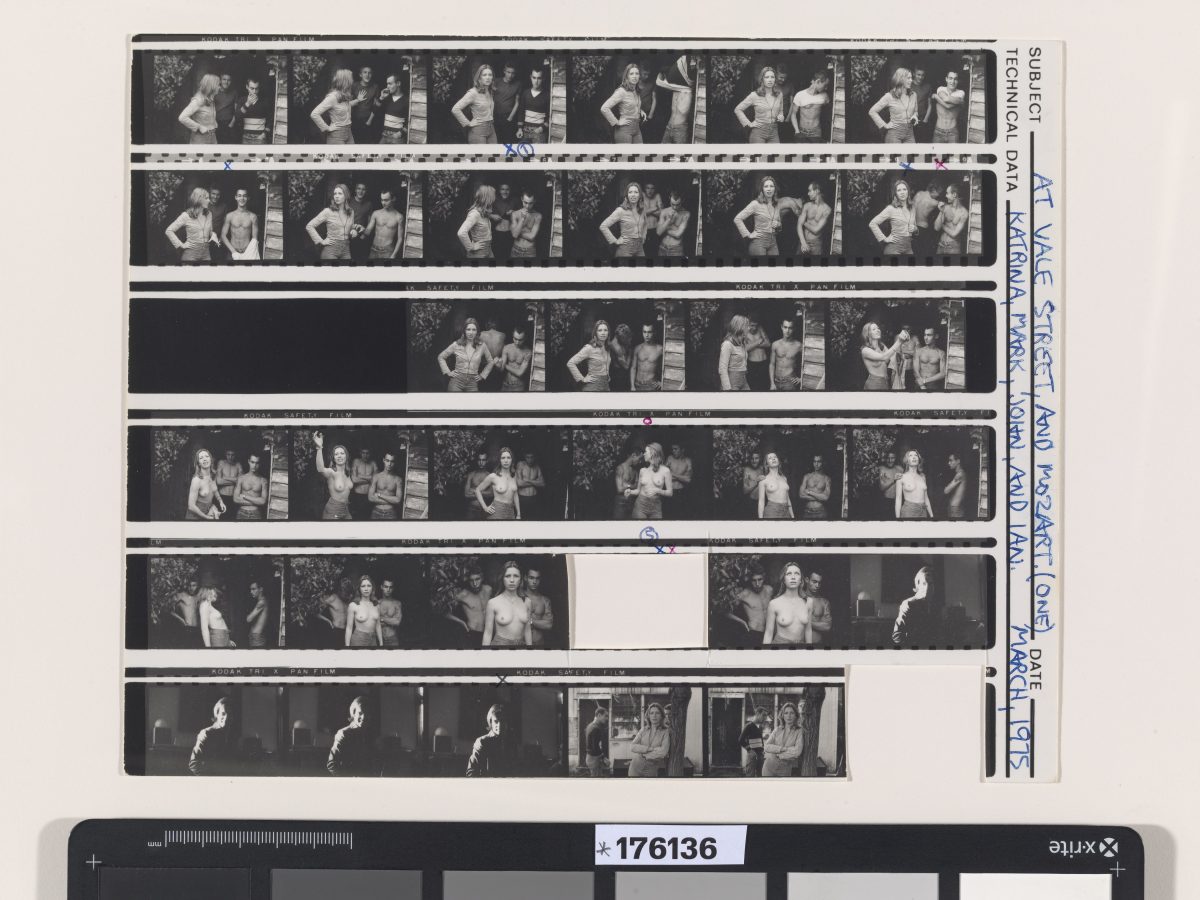

Jerrems’ Vale Street, 1975, became an iconic image shortly after the photograph was made. The photographic contact sheets (prints made directly from the strips of film without enlargement or editing) – exhibited alongside the chosen final print – demonstrate how deliberately Jerrems constructed her image.

Aspiring actress Catriona Brown was introduced by the photographer to her two Sharpie students from the Heidelberg Technical College and posed within a suburban backyard.

Carol Jerrems, Contact sheet, Vale Street, Mozart St, Ian Macrae, 1975, National Gallery of Australia, © The Estate of Carol Jerrems. Photo: National Portrait Gallery.

Posed naked from the waist up, the figures in this black and white photograph stare directly at the viewer and engage our gaze.

Jerrems observed: “The world is in a mess. You either drop out or help to change it. I want to focus on … all the things that people don’t want to talk about or know about … A face tells the story of what people are thinking.”

Jerrems had the gift of creating a sense of informality despite her carefully staged procedure. To some, Vale Street became the icon of Australia’s women’s liberation movement of the 1970s. Others saw this print, shortly after it was made, as the feminist response to the display of heroic male masculinity in Max Dupain’s Sunbaker, 1937.

Jerrems’ Vale Street was printed in an edition of nine and priced at $45 per print. Last year, a print from this edition was sold for $122,000, making it the most expensive Australian photograph ever sold. It has become the poster image of a generation and looms large in accounts of Australian art history.

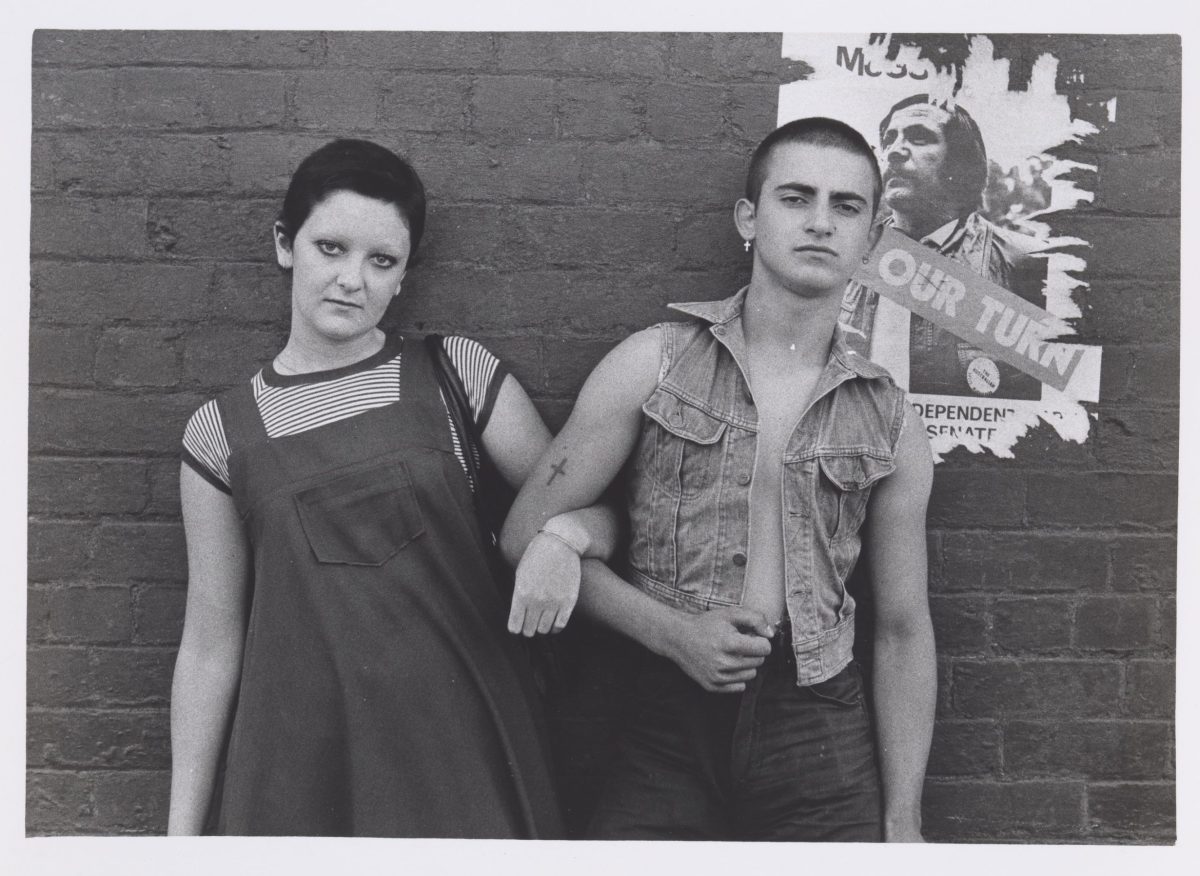

Carol Jerrems, Sharpie couple, Melbourne, 1976, gelatin silver photograph, 17.9 x 25.3cm, National Gallery of Australia © The Estate of Carol Jerrems. Photo: National Portrait Gallery.

What was the achievement of Jerrems?

Isobel Parker-Philip, a co-curator of this exhibition, writes: “To turn back to Jerrems’ photographs, 45 years after her death, is to consider what lingers. Jerrems amplified the narrative potential of the quiet moment and saw tenderness and intimacy as deserving of attention.”

Whereas many photographic exhibitions are particularly ‘noisy’, there is a quiet stillness in Jerrems’ work, an intimacy and silent reflection.

While Jerrems documented the world around her and was rarely separated from her camera, she was not strictly a documentary photographer. Her narratives are generally posed and carefully constructed, the multiplicity of photographs of the same subject demonstrates the deliberateness of her approach.

Magda Keaney, the exhibition’s other co-curator, engages in her essay with the question of Jerrems as the insider photographing her milieu without becoming a social documentary photographer producing work that will be used for political change.

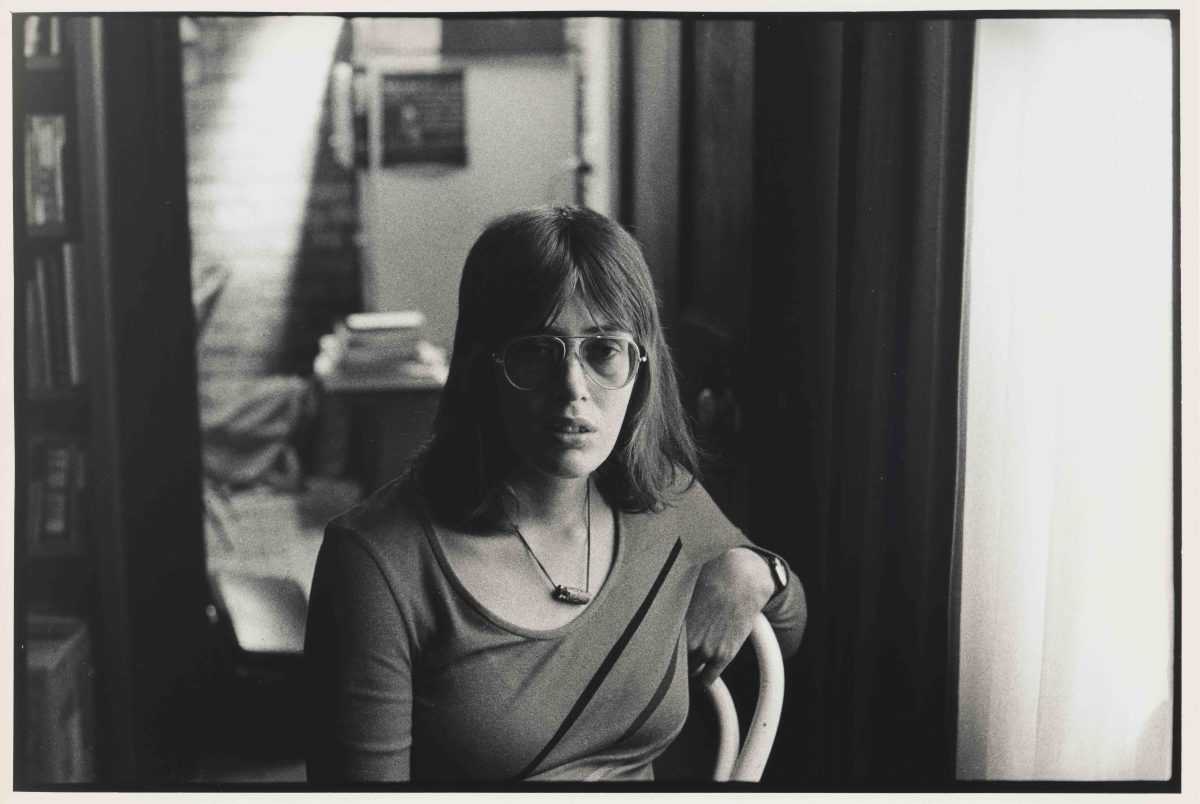

Carol Jerrems, Portrait of Anne Summers, 1974, gelatin silver photograph, 16.2 x 24.2cm, National Portrait Gallery © The Estate of Carol Jerrems. Photo: National Portrait Gallery.

Jerrems was not the tourist outsider with a camera snapping whatever caught her eye; she photographed a reality she knew well – frequently intimately – but also created an emotional distance in her photographs.

A Sharpie couple Melbourne, 1976, is a photograph of people she knew well, now posed to appear typical of a social phenomenon rather than a couple of individual portraits. Her Portrait of Anne Summers, 1974, is a clever, posed study that has the appearance of a candid snap.

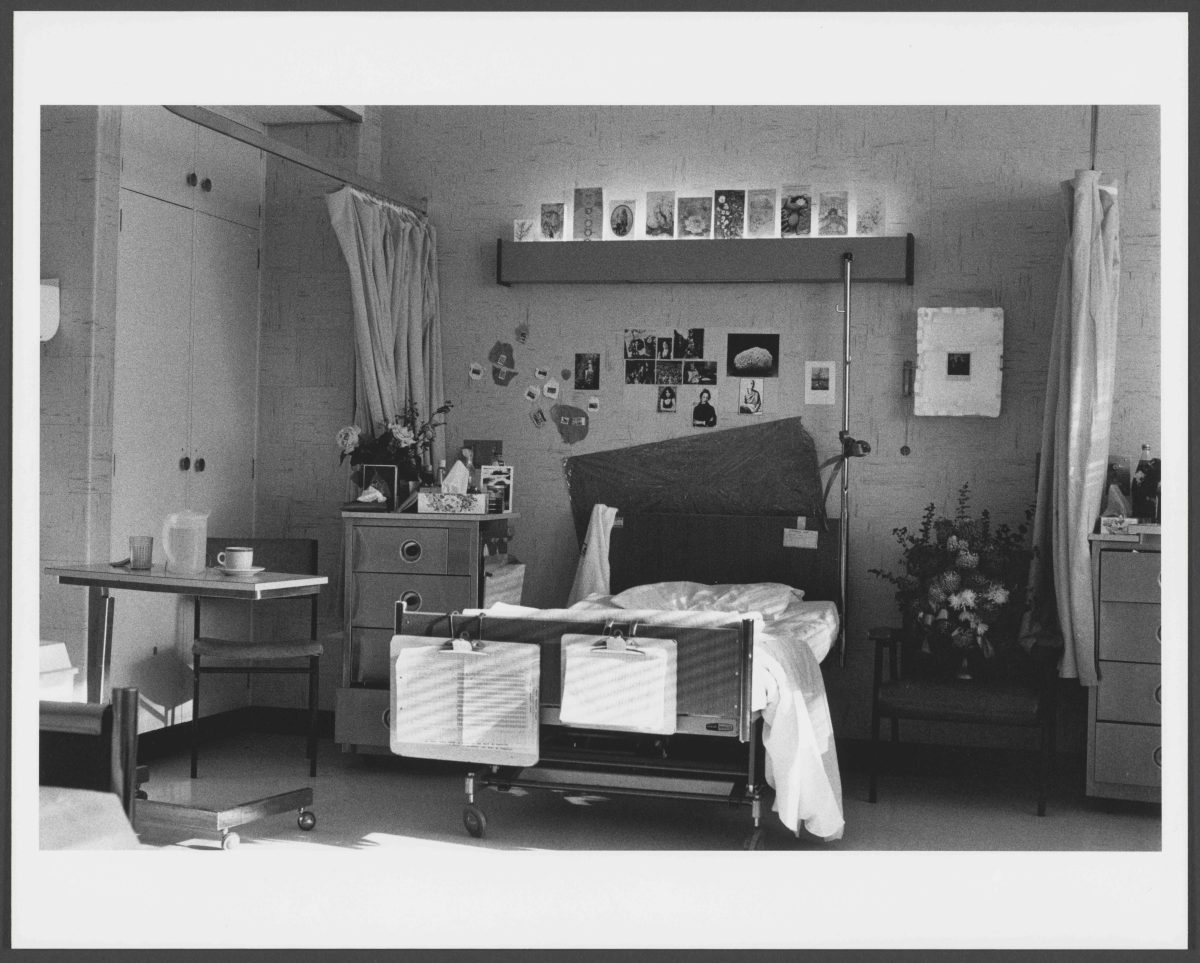

The exhibition is studded with self-portraits, including Self-portrait, 1973, (sitting on the edge of the bed while her lover is still asleep in the bed) or the traumatic Carol Jerrems’ bed with personal effects, Royal Hobart Hospital, 1979 – a study of a cluttered emptiness as the artist confronts her death.

Carol Jerrems, Carol Jerrems’ bed with personal effects, Royal Hobart Hospital, 1979, gelatin silver photograph, 16.1 x 24.2cm, National Library of Australia © The Estate of Carol Jerrems. Photo: National Portrait Gallery.

Jerrems had a distinct photographic personality. Navigating your way around the exhibition you can hear her unique voice as you move from image to image. They are low-tech photographs, most shot with a 35mm Pentax Spotmatic single-lens reflex camera with a standard f1.4 50mm on black and white film and printed by the artist herself. She used colour infrequently.

The exhibition is a profoundly moving experience. There is nothing bombastic or that screams in your face, but a quiet affirmation of the dignity of being human.

Jerrems once observed: “I don’t want to exploit people. I care about them; I’d like to help them if I could, through my photographs.”

Carol Jerrems: Portraits is on now at the National Portrait Gallery, King Edward Terrace, Parkes daily 10 am to 5 pm until 2 March.

Tickets: Adult $20 / Concession $18 / Circle of Friends $16 / Under 30s $10 / Under 18s free. Bookings available via National Portrait Gallery.