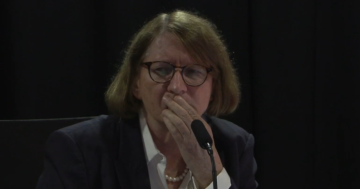

Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus said the legislation “provides strong protections for whistleblowers and exemptions for journalists to protect the identity of their sources”. Photo: ALP.

Public service whistleblowers will have protection and agency heads will be required to report corruption once a new federal anti-corruption watchdog is established.

The Federal Government has introduced its legislation for a national anti-corruption commission, which looks to have a successful passage through both houses of parliament.

The Opposition has already signalled its support for the model Labor has put up, which includes an insistence that the commission holds most of its hearings behind closed doors.

The proposed commission would comprise a commissioner, three deputy commissioners and a secretariat headed by a chief executive.

It will be funded with $262 million over four years, with strong parliamentary oversight of its expenditure, but have independence in its operations.

A parliamentary committee will approve the appointment of the commissioner.

Under the legislation, as it currently stands, public service whistleblowers would be legally protected.

Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus stressed that point before introducing the bill.

“The legislation also provides strong protections for whistleblowers and exemptions for journalists to protect the identity of their sources,” Mr Dreyfus said.

“The National Anti-Corruption Commission bill will have its own whistleblower protections, as is appropriate for Australian public servants and people working in the public sector, who come forward with allegations that the commission should look at.”

Those provisions appear to have appeased some crossbench senators, although concerns are being expressed about the secrecy of the commission’s hearings.

The government has included the Coalition’s proposal for in-camera hearings to win Opposition support and not have to convince independents and the Greens to support the legislation.

Mr Dreyfus said public hearings would only be held in exceptional circumstances and only after the commission had considered the public interest of a case.

“Most of the hearings conducted by this federal commission, just as for the state and territory commissions, will be conducted in private,” he said.

“We think that is the right setting, and it shows that the commission has to take that into account before it decides to hold a public hearing, but it will remain a matter for the commissioner.”

Investigations would be conducted following complaints, referrals, or off its own bat if the commission believed there was serious or systemic corruption to be dealt with.

Public service heads would be required by law to report corruption to the commission.

Speaking to that point, Mr Dreyfus said the commission would have powers similar to a royal commission and be able to “compel the production of information” to determine the seriousness of an allegation.